Locating Causal Reasoning Circuits in Large Language Models

Introduction

Recent work by Lee et al. has taken initial steps in analyzing the circuits used by transformer-based large language models (LLMs) for simple causal reasoning tasks. Their study focused on clear-cut cause-and-effect sentences like “John had to pack because he is going to the airport” and analyzed causal interventions on GPT-2 small. They demonstrated that causal syntax, such as “because” and “so”, is captured in the first few layers of the model, while later layers focus on semantic relationships to perform simple causal reasoning tasks.

In this study, we extend this analysis by investigating:

- How semantic reasoning is processed across LLMs of varying sizes, beyond just GPT-2 small.

- The similarities and differences between semantic and mathematical reasoning circuits, identifying whether LLMs use distinct or overlapping attention heads for these tasks.

Our findings suggest that while LLMs consistently localize causal syntax in early layers, different models allocate reasoning tasks to distinct attention heads depending on their scale. Furthermore, we observe structural parallels between semantic and mathematical reasoning, with mathematical processing typically occurring in deeper layers and requiring more distributed computation across attention heads. These insights contribute to a broader understanding of how LLMs perform causal reasoning tasks.

Code and data can be found here.

Methods

To investigate causal reasoning mechanisms across LLMs, we performed the main steps as proposed by Lee et al. with extentions to different model sizes and mathematical reasoning. Our main steps are as follows:

- Dataset Creation: We developed a syntactically controlled dataset using two templates:

- Effect-because-Cause: \([e_1,\ldots,e_n, d, c_1,\ldots c_m]\)

- Cause-so-Effect: \([c_1,\ldots c_m, d, e_1,\ldots,e_n]\)

where \(c_i\) represents cause tokens, \(d\) is the causal delimiter (“because” or “so”), and \(e_j\) represents effect tokens. For example: “Alice went to the craft fair because she wants to buy gifts.”

- Attention Analysis: We quantified causal reasoning by measuring:

Attention paid to causal delimiters (\(P_d\)): \(P_d = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^m \alpha_{d,j}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n+m+1}\sum_{j=1}^{n+m+1} \alpha_{i,j}}\)

Proportion of cause-to-effect or effect-to-cause attention (\(P_c\)): \(P_c = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^m \alpha_{i,j}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n+m+1}\sum_{j=1}^{n+m+1} \alpha_{i,j}}\)

where \(\alpha_{i,j}\) represents attention weights calculated using standard transformer attention mechanisms.

- Activation Patching Analysis: We employed activation patching to understand how different model components contribute to causal and mathematical reasoning:

- Clean vs Corrupted Inputs: For each template, we created pairs of “clean” (correct) and “corrupted” (incorrect) inputs by systematically replacing key tokens

- Patching Process: We ran the model on both clean and corrupted inputs, then patched activations from the clean run into the corrupted run to measure each component’s contribution to the output logits.

- Metric: We used a calibrated logit difference metric that equals 0 when performance matches corrupted input and 1 when matching clean input.

- Template Categories: We developed two sets of controlled templates to test different reasoning capabilities:

- Semantic Templates:

- ALB: Action-Location-Because relationships (e.g., “John had to [action] because he is going to the [location]”)

- AOB: Action-Object-Because relationships

- ALS/ALS-2: Action-Location-So relationships

- AOS: Action-Object-So relationships

- Mathematical Templates:

- MATH-B-1/2: Basic addition problems

- MATH-S-1/2/3: Subtraction and logical sequence problems

The full template specifications are detailed in Appendix B and C.

- Semantic Templates:

- Comparative Study Across Model Sizes: We analyzed these patterns across GPT-2 variants, including GPT-2 small, medium, large, and XL.

Locating Causal Syntax in LLMs

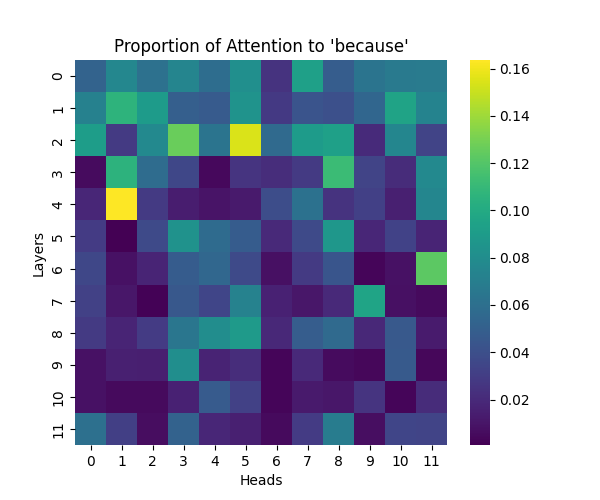

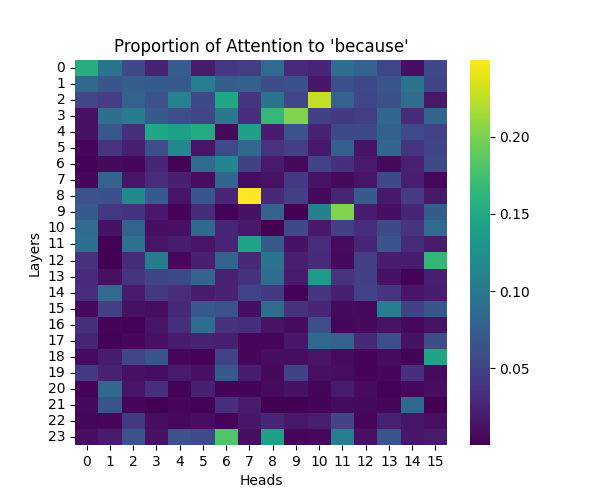

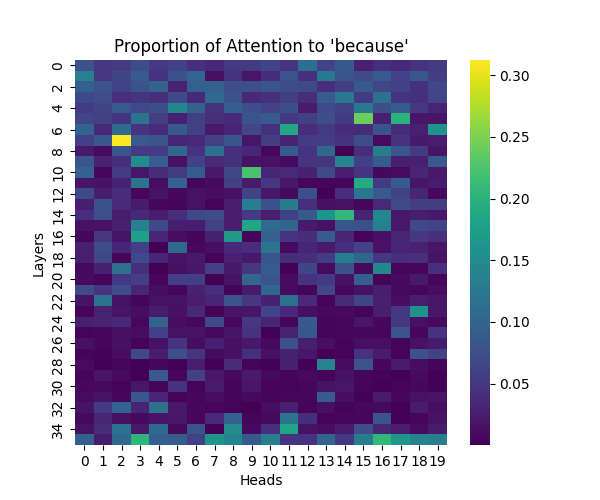

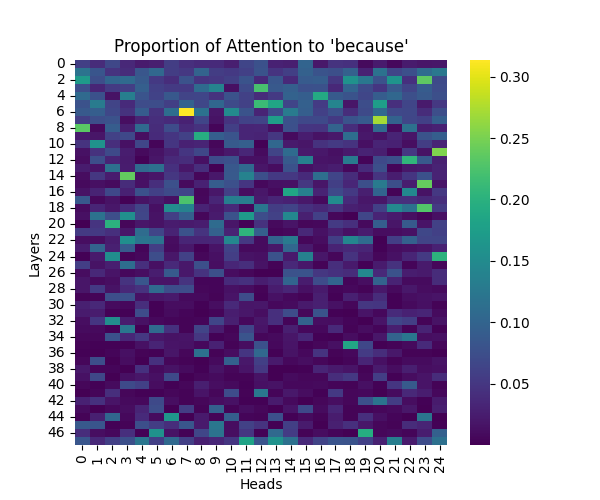

For sake of brevity, we only show the results for the “because” template, please see Appendix A for the other template results which showcase similar patterns.

Figure 1: Attention to “Because” Token Across Model Scales

GPT-2 Small | GPT-2 Medium |

GPT-2 Large | GPT-2 XL |

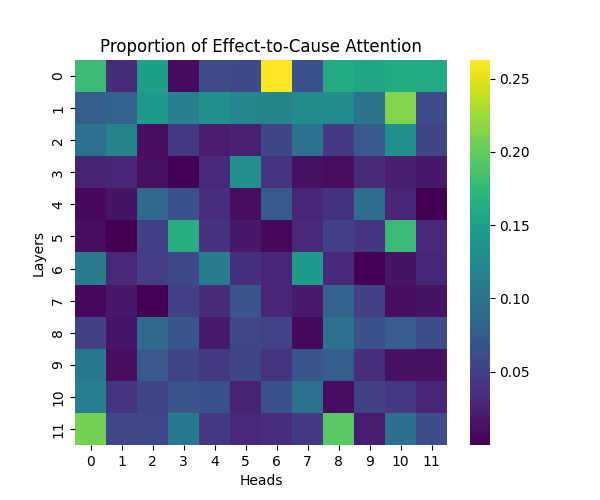

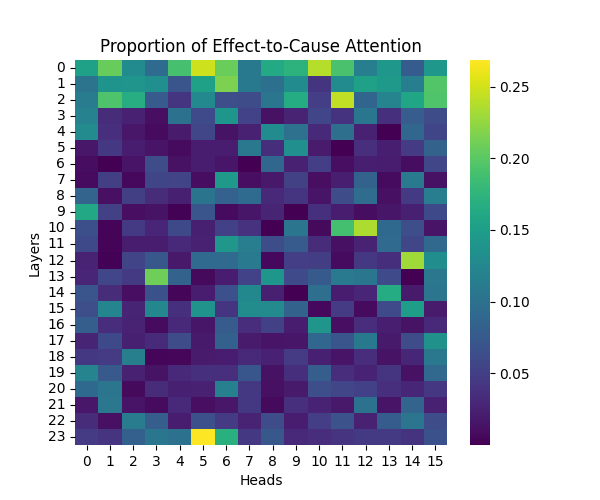

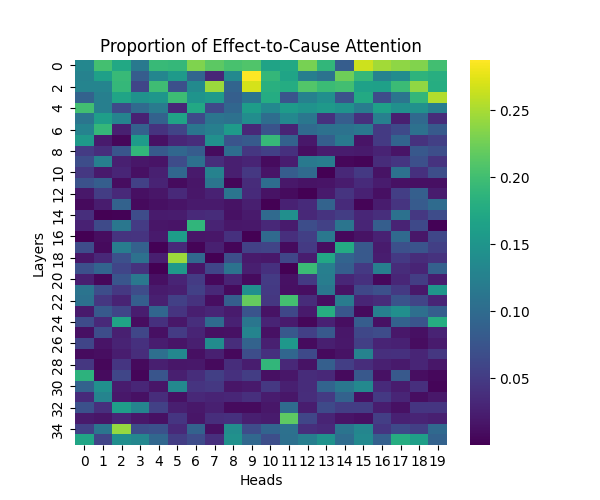

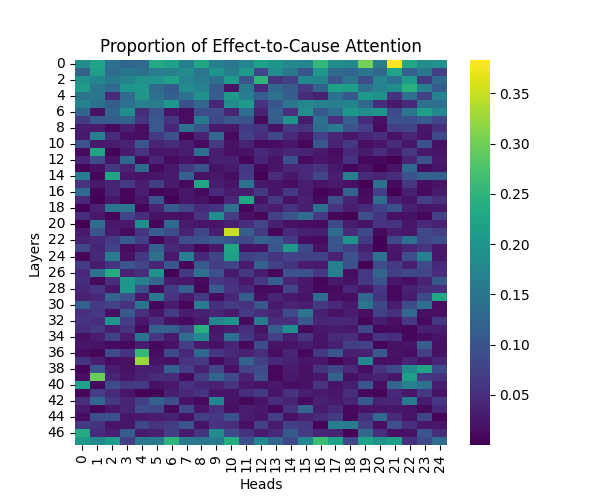

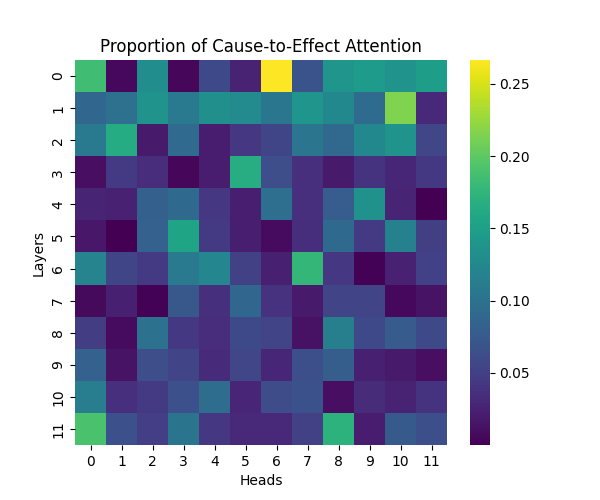

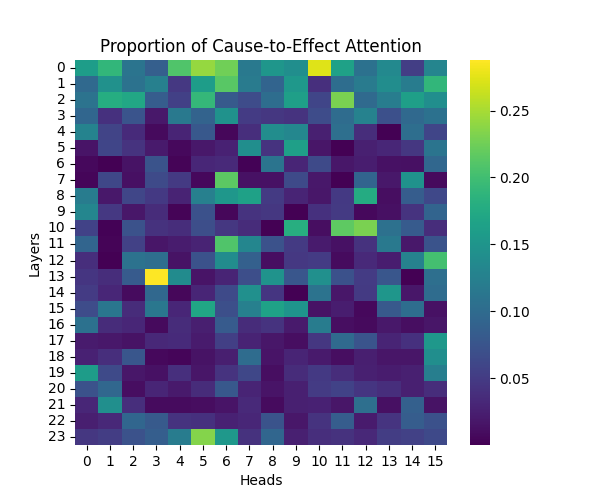

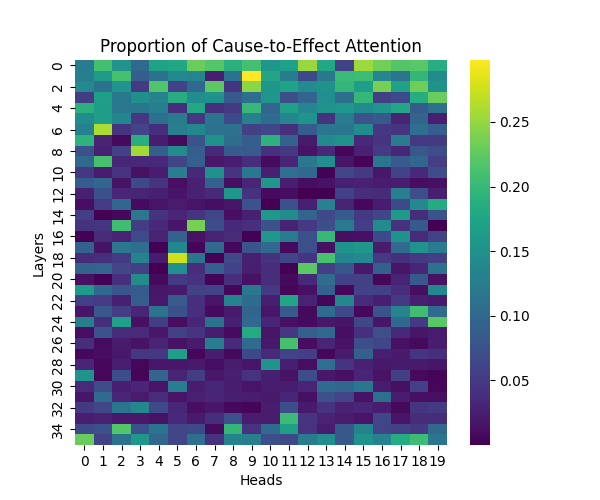

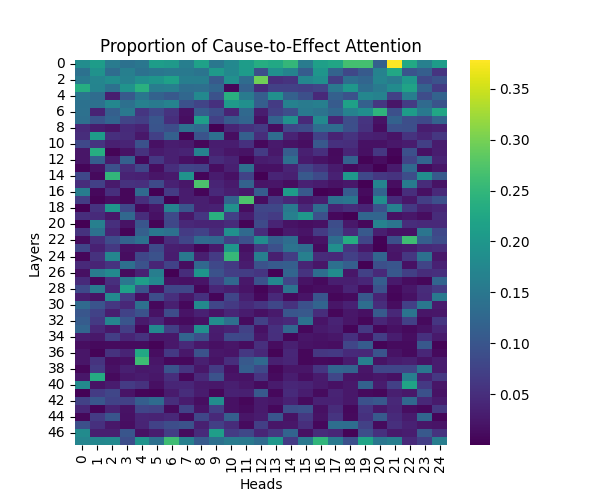

Figure 2: Effect-to-Cause Attention Patterns Across Model Scales

GPT-2 Small | GPT-2 Medium |

GPT-2 Large | GPT-2 XL |

Discussion

Our analysis builds upon the findings of Lee et al., who initially observed that causal syntax processing occurs primarily in the early layers of GPT-2 Small. When extending this investigation across larger model scales, we found this pattern holds consistently true: the processing of both causal markers (like “because”) and effect-to-cause relationships remains concentrated in the early layers across all model sizes.

This consistent localization of syntactic processing in early layers appears to be a fundamental architectural feature of these models, independent of scale. This finding suggests that the basic mechanisms for processing causal syntax may be similar across different model sizes.

Locating Semantic Reasoning

We performed activation patching analysis across GPT-2 variants to identify specific attention heads responsible for semantic processing. Our analysis examined attention patterns when processing semantic relationships, focusing on head-specific activations and their consistency across different semantic contexts. The results shown here represent averages across all templates; individual template results can be found in Appendix B.

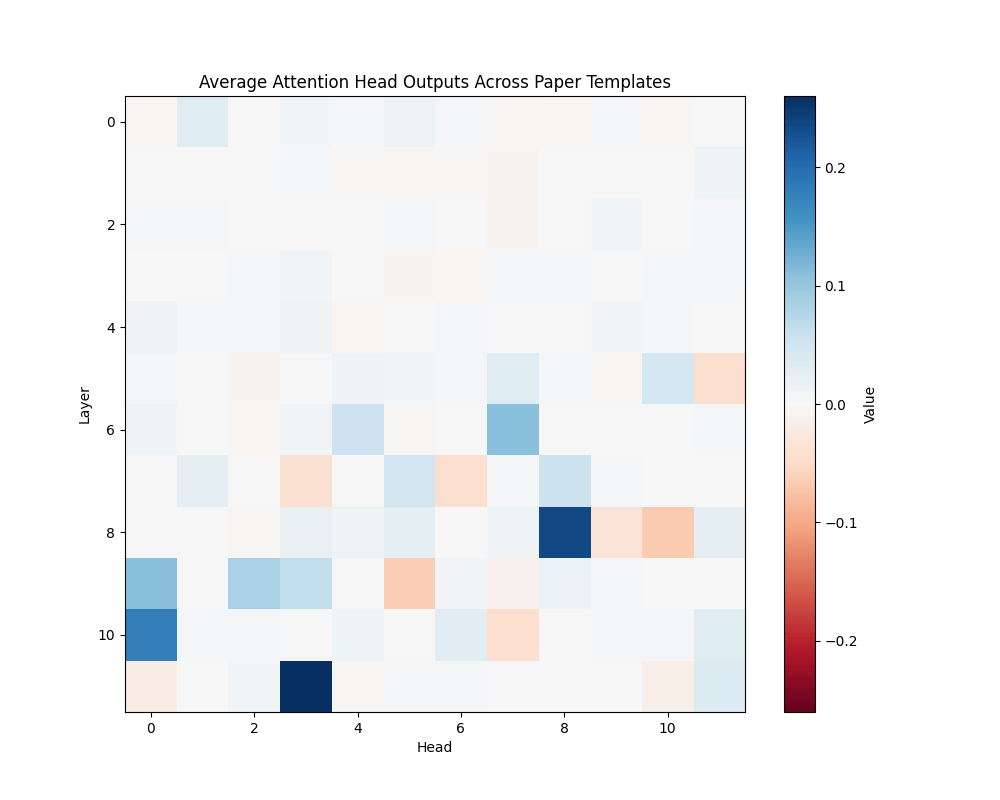

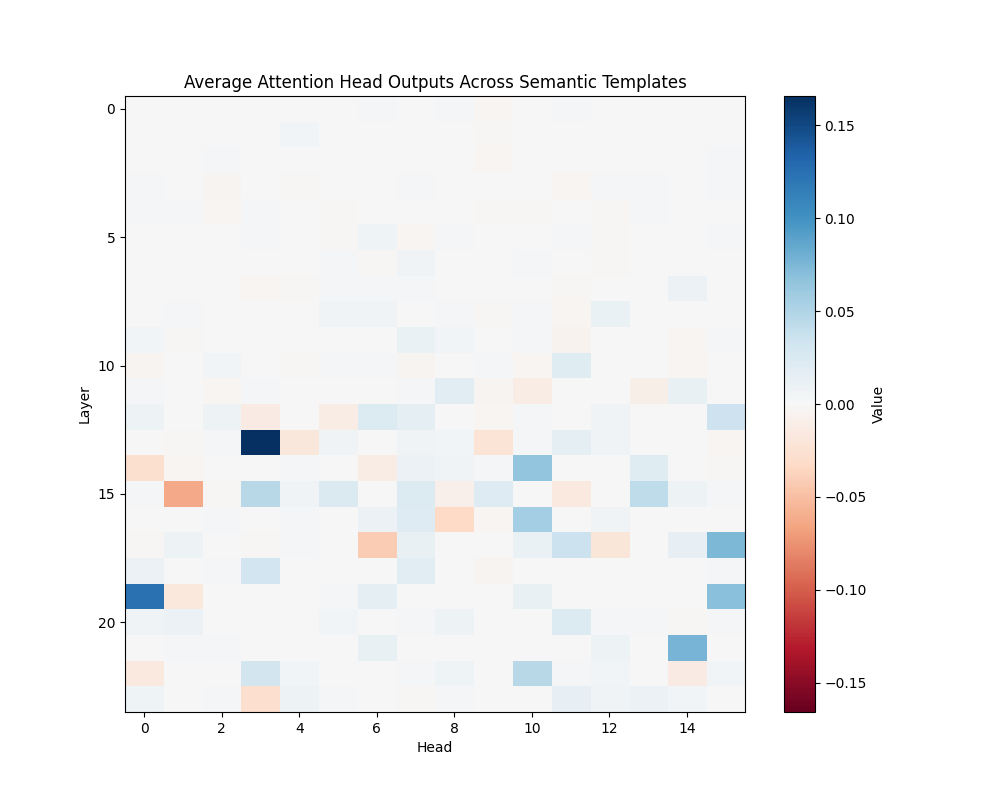

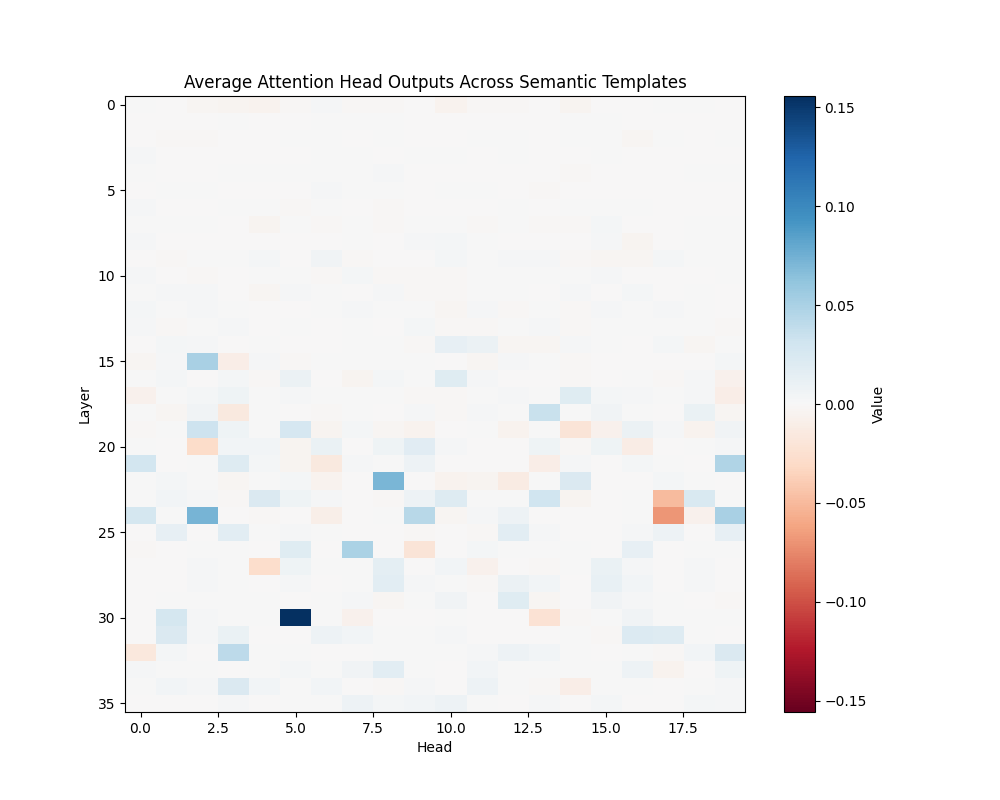

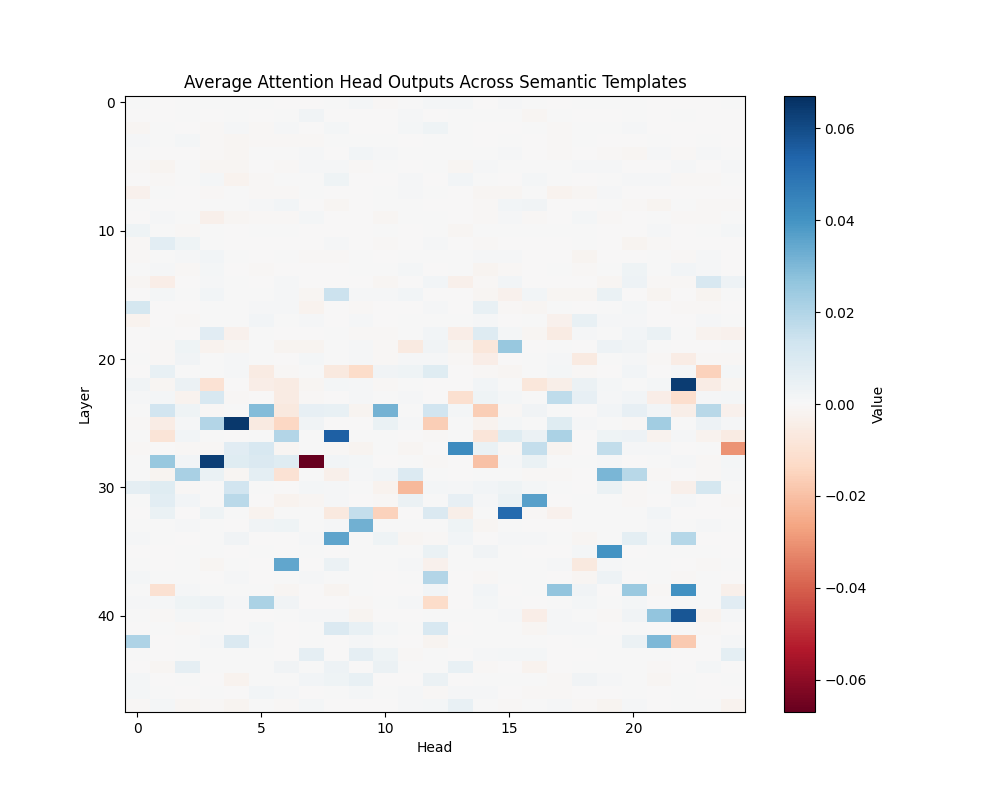

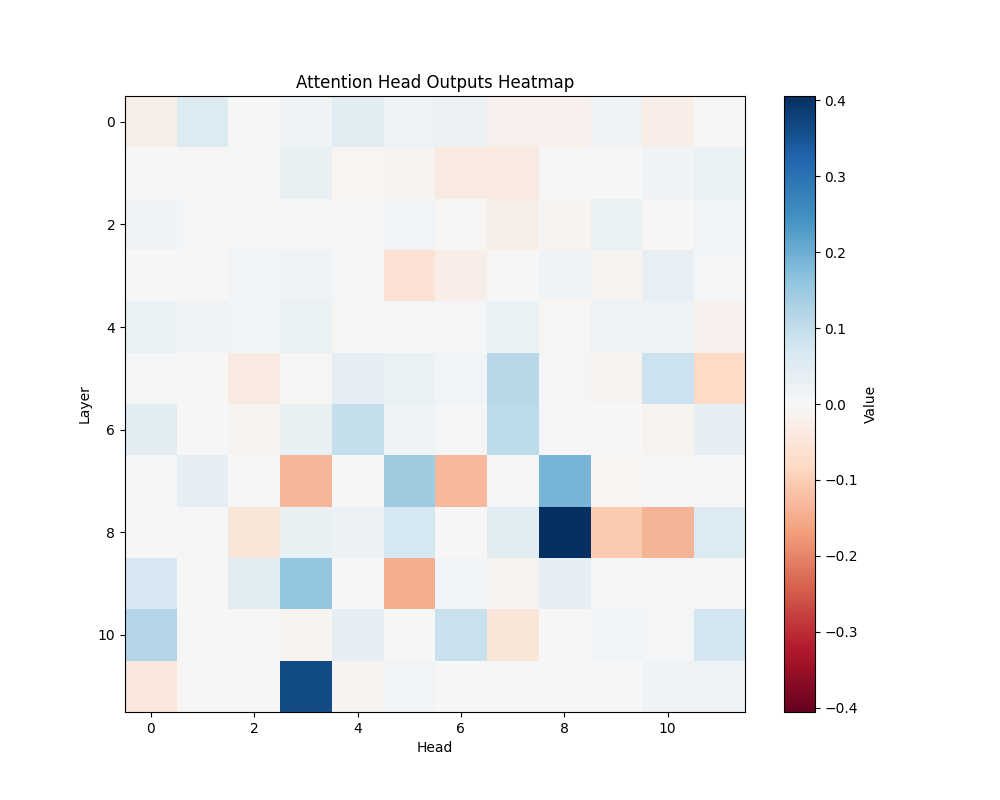

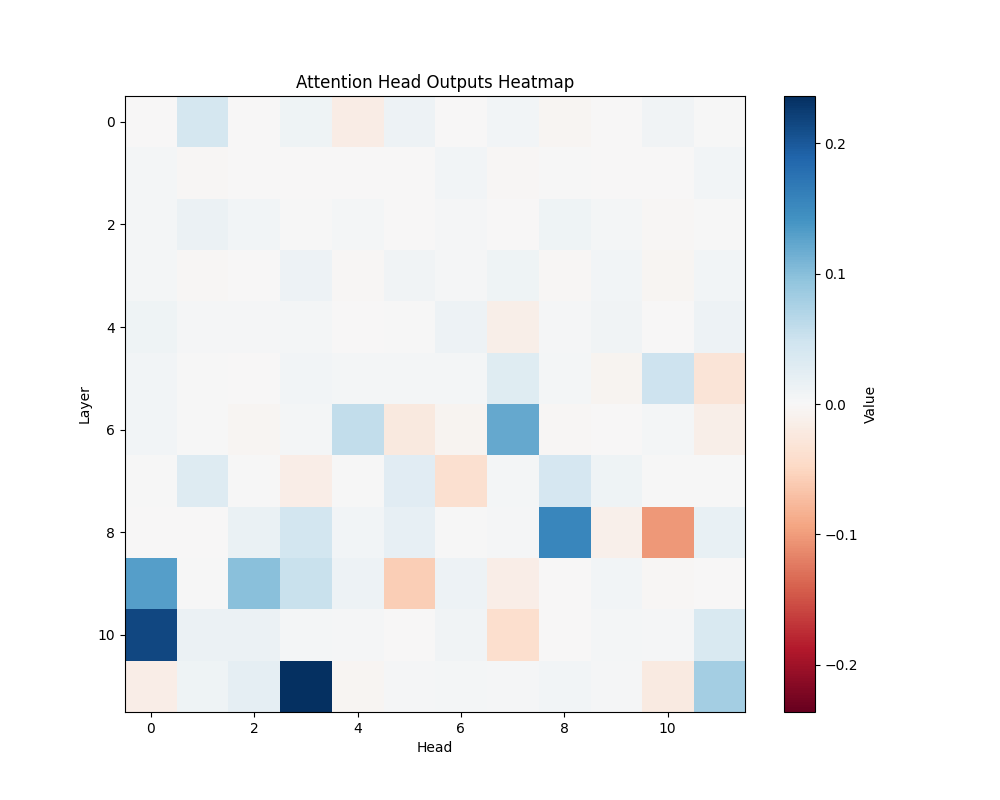

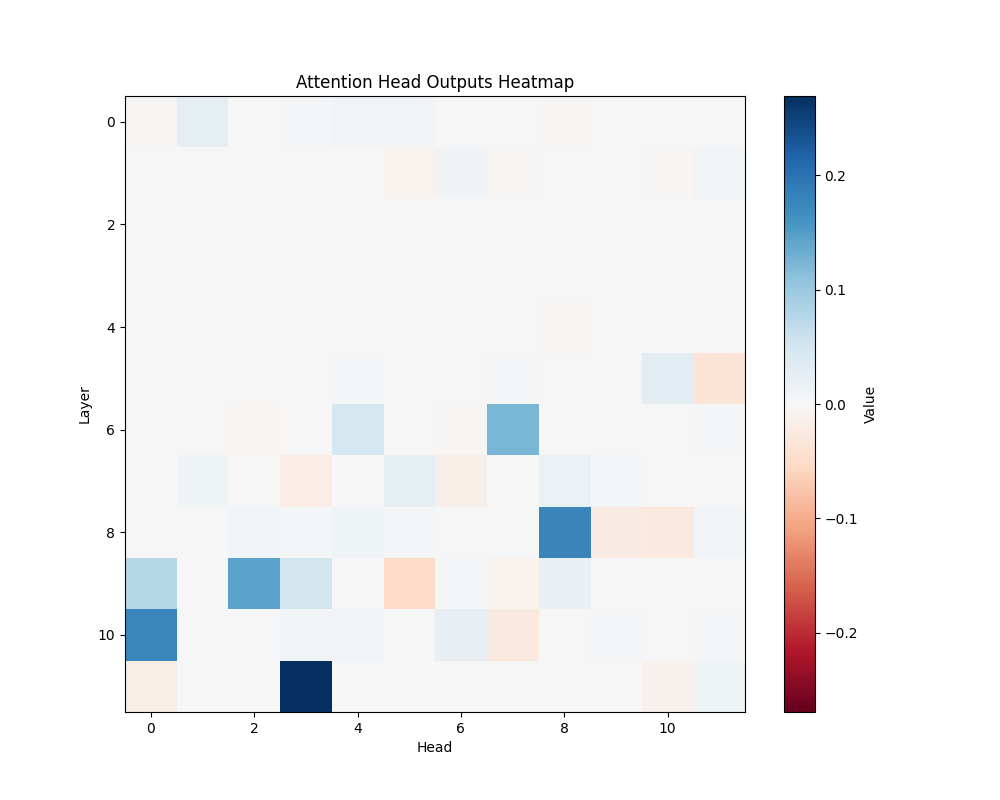

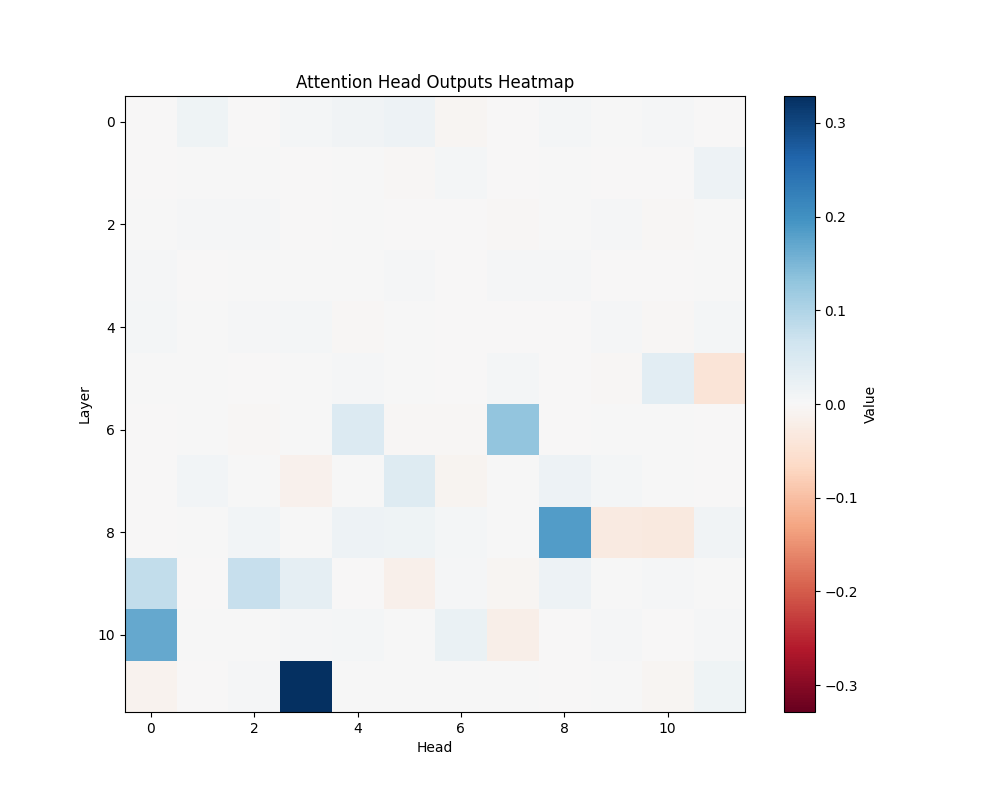

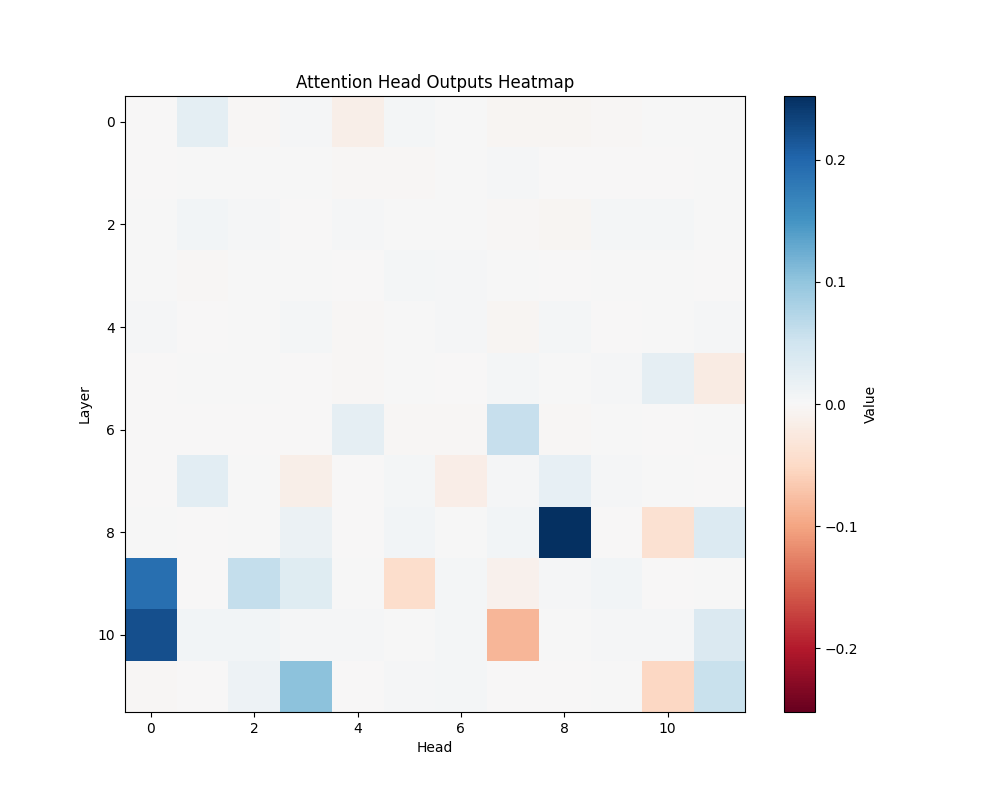

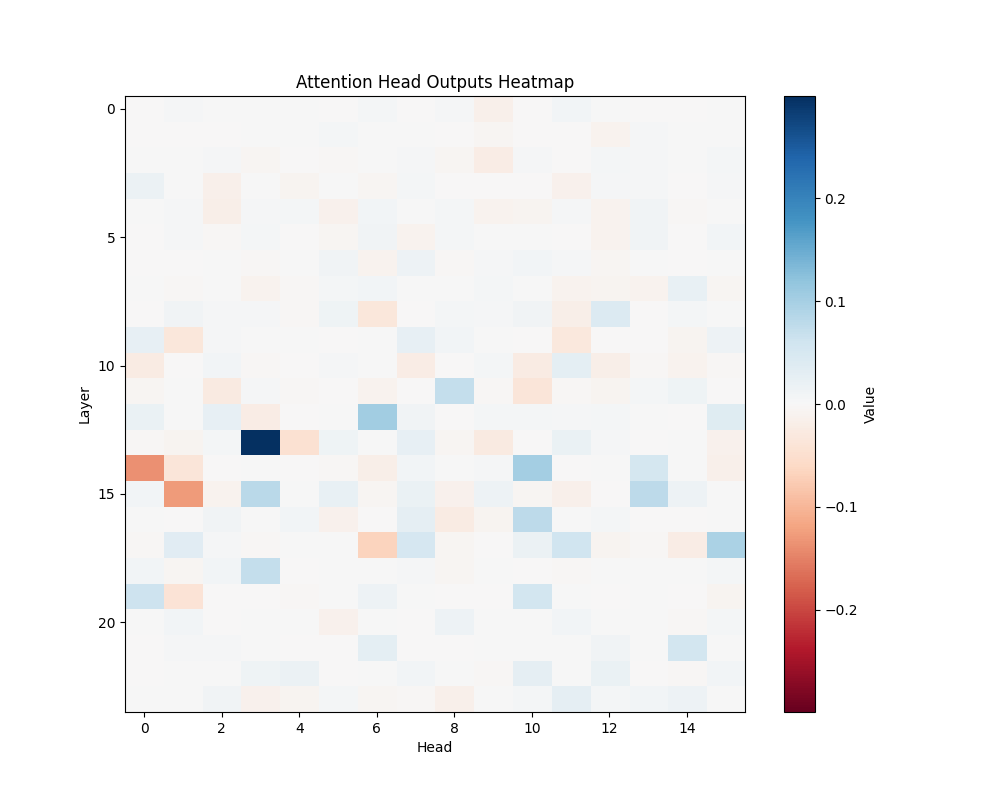

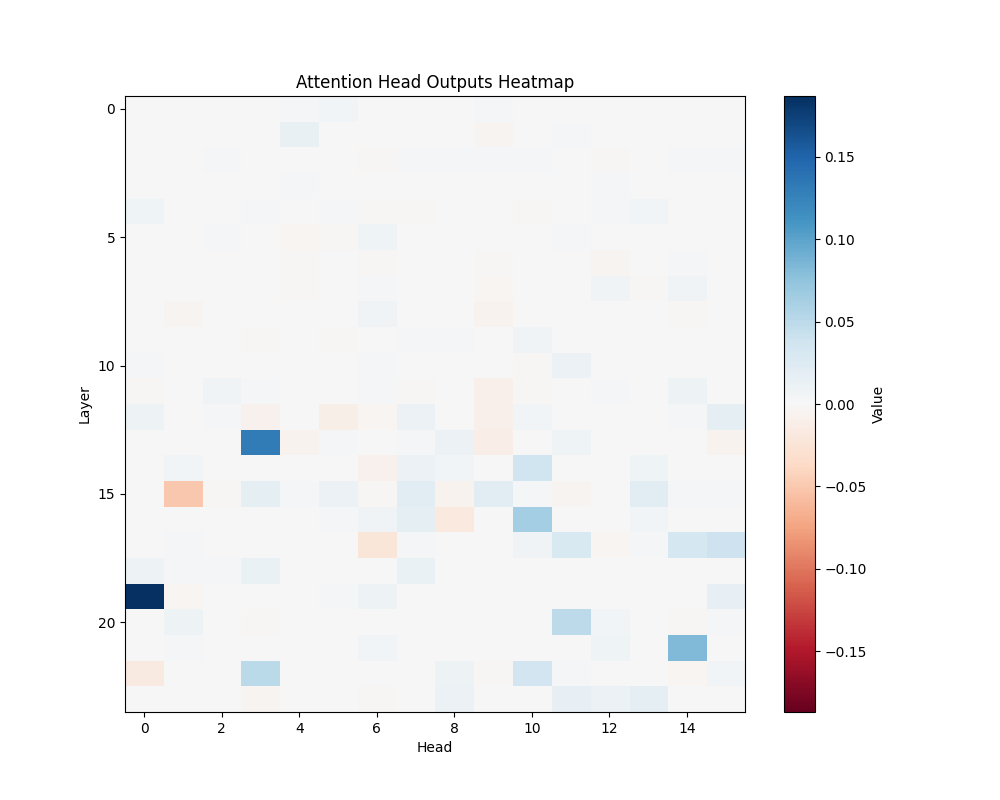

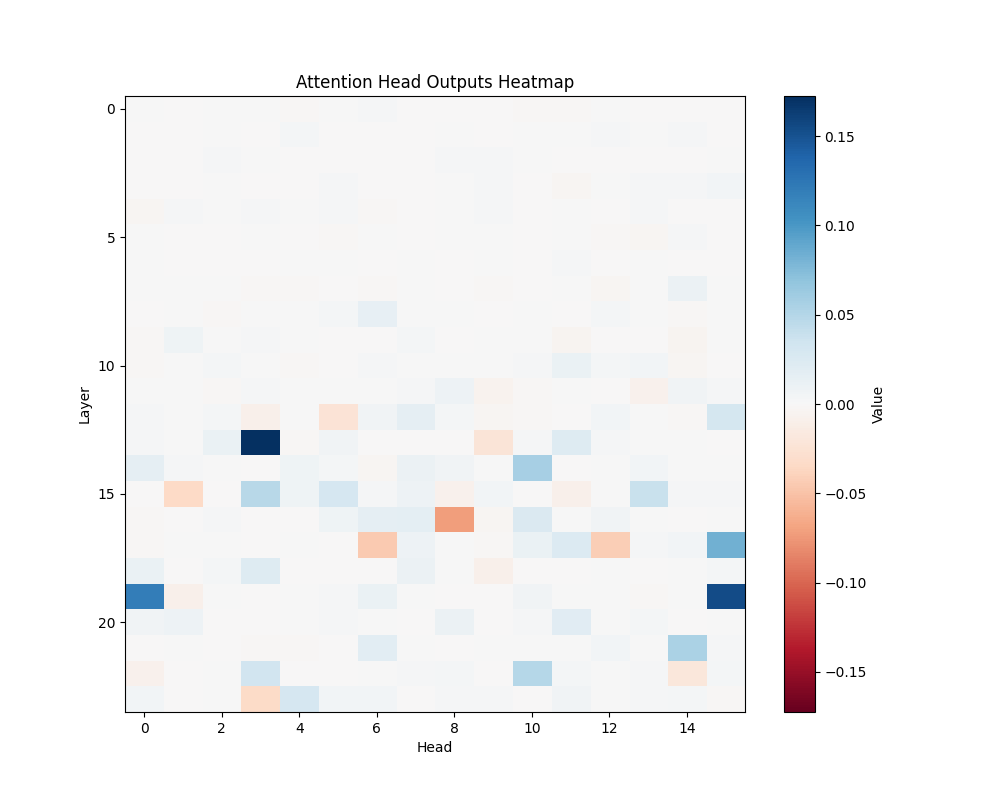

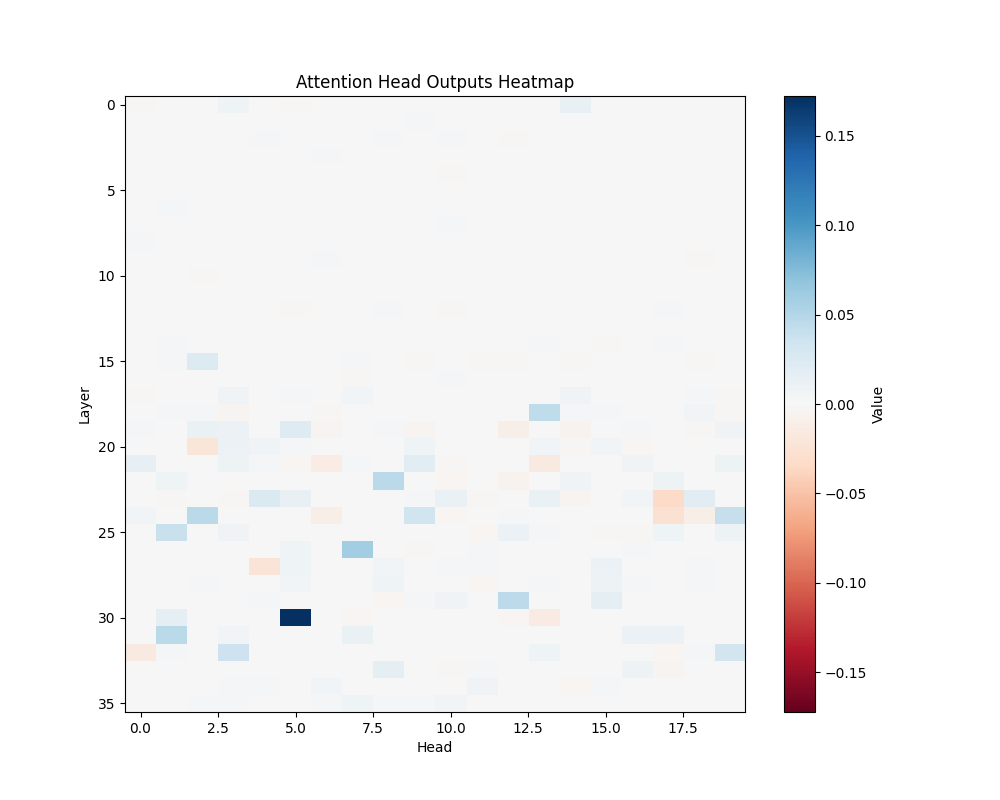

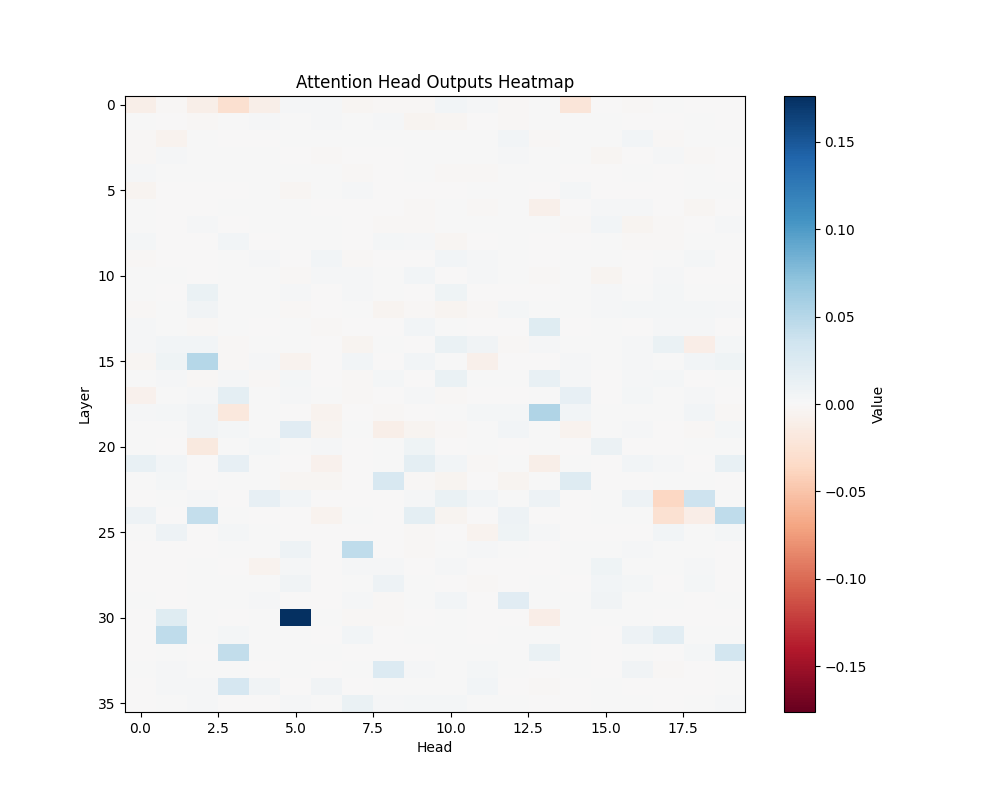

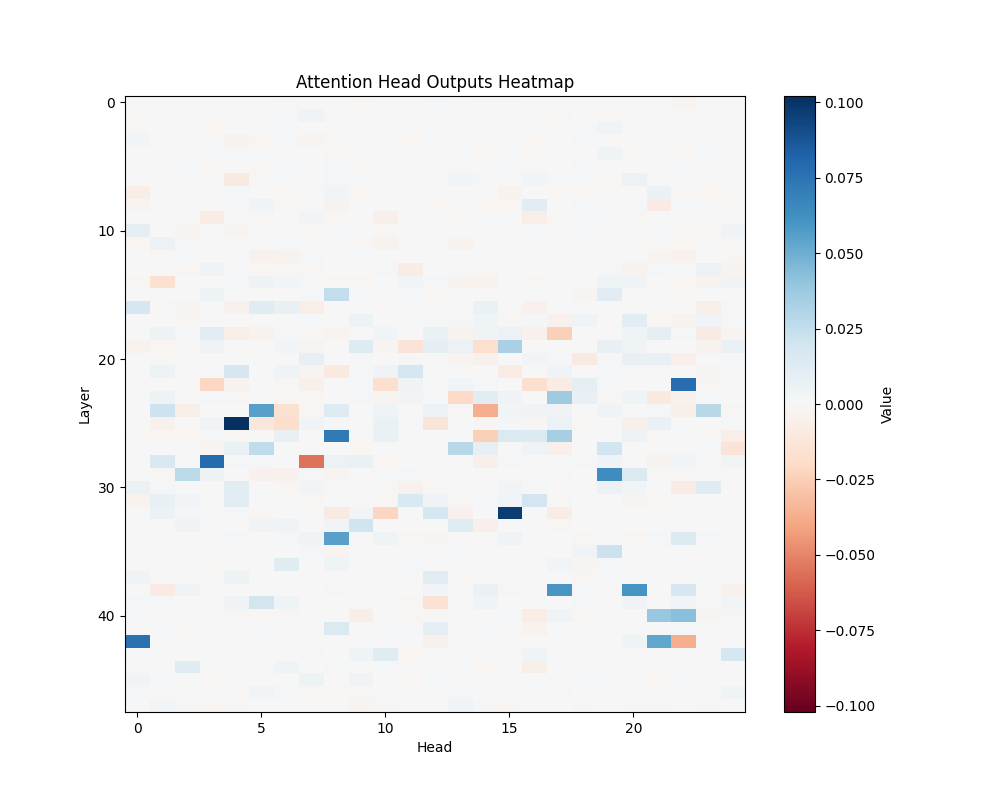

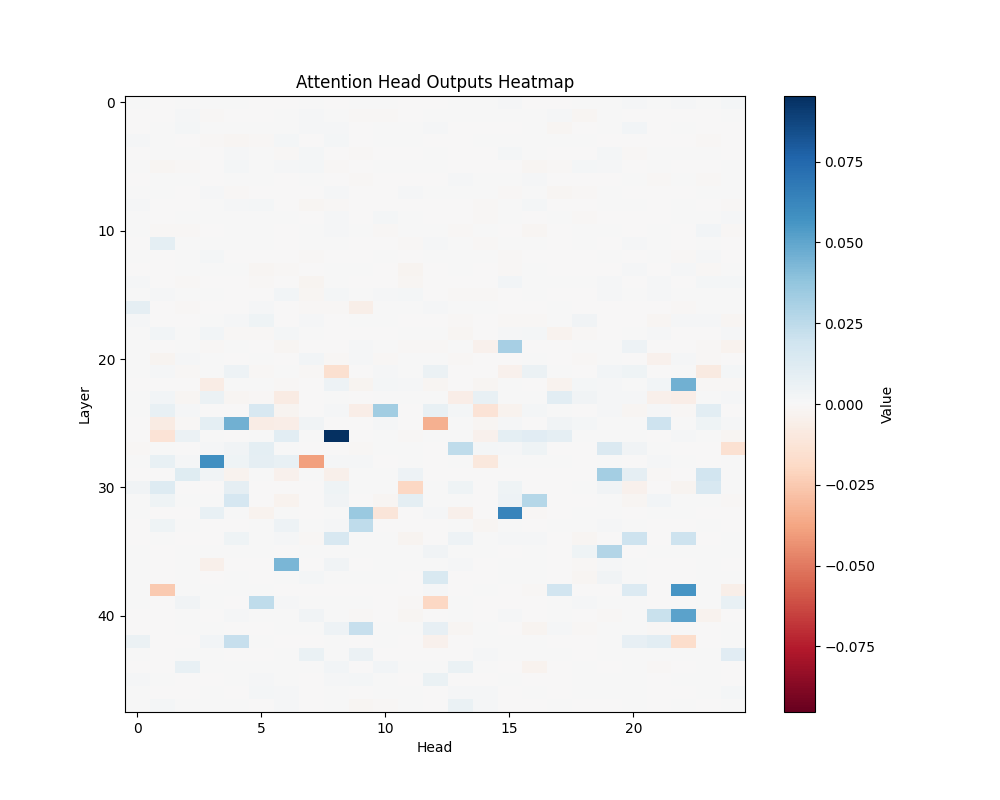

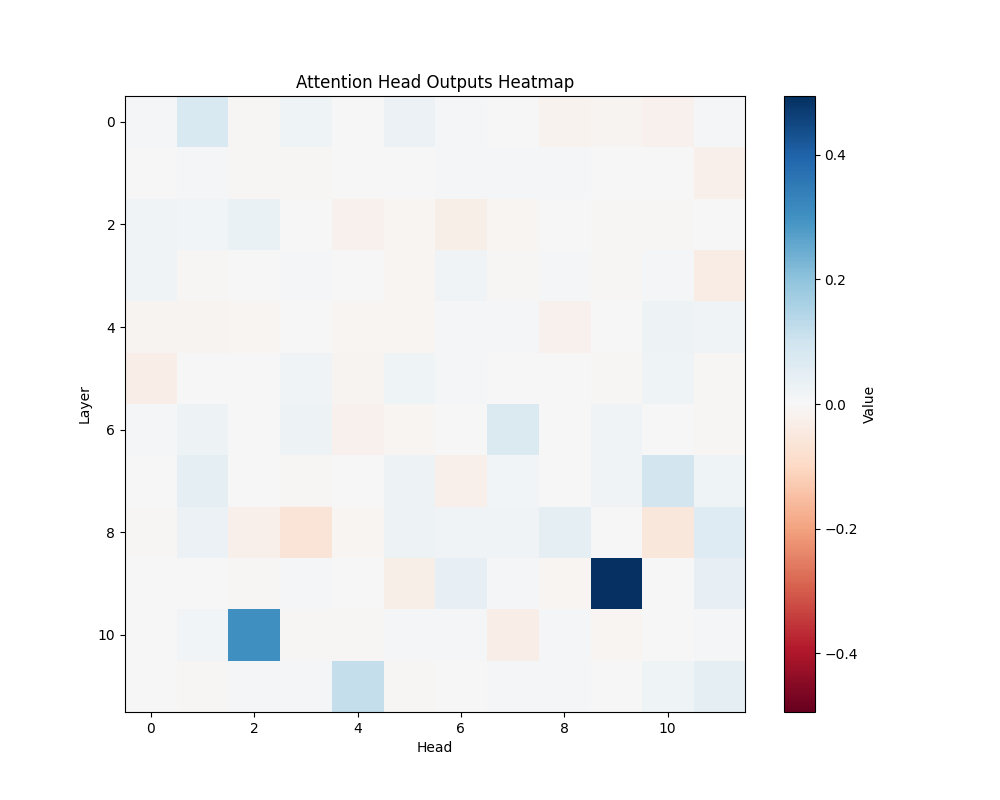

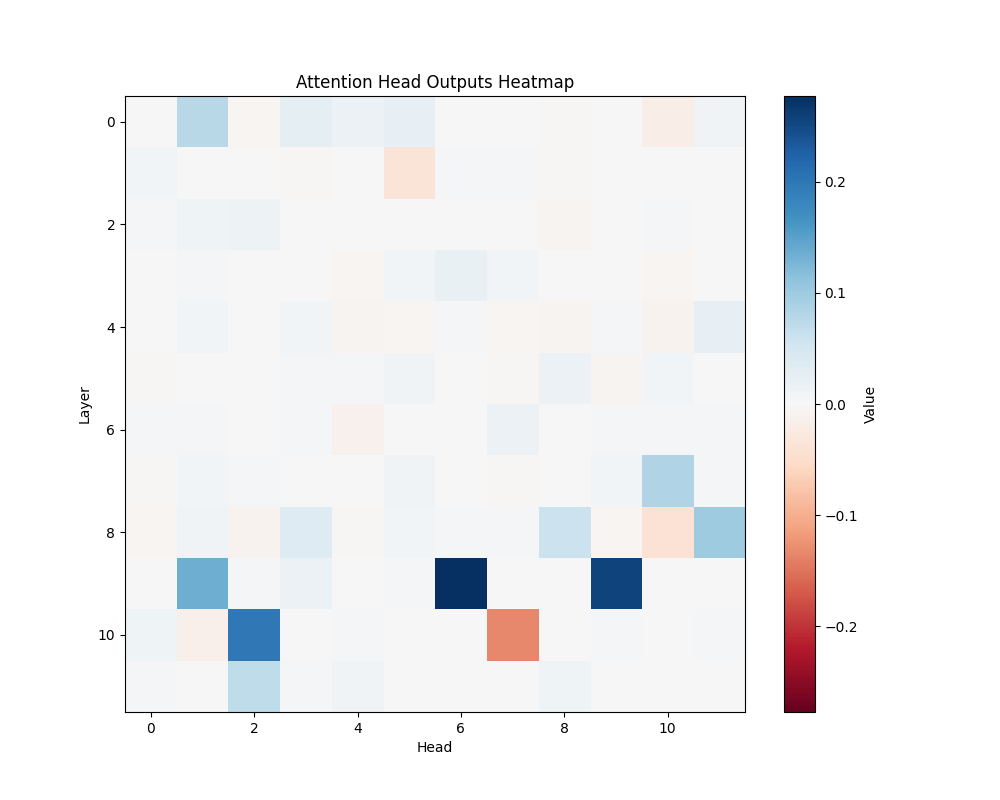

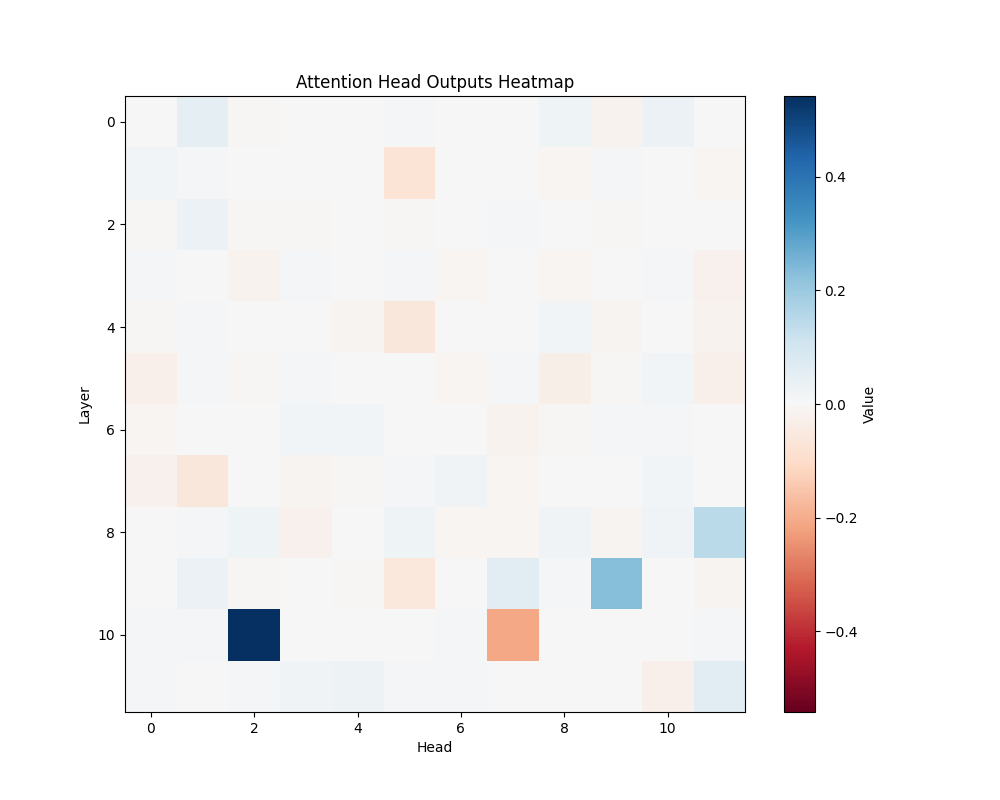

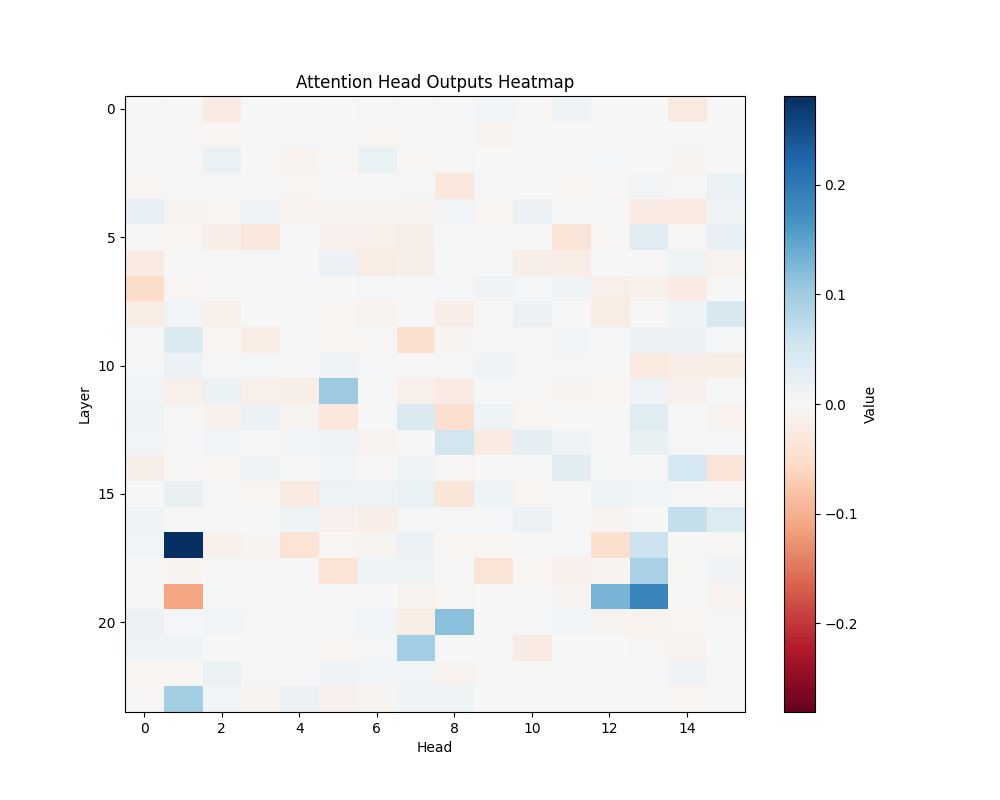

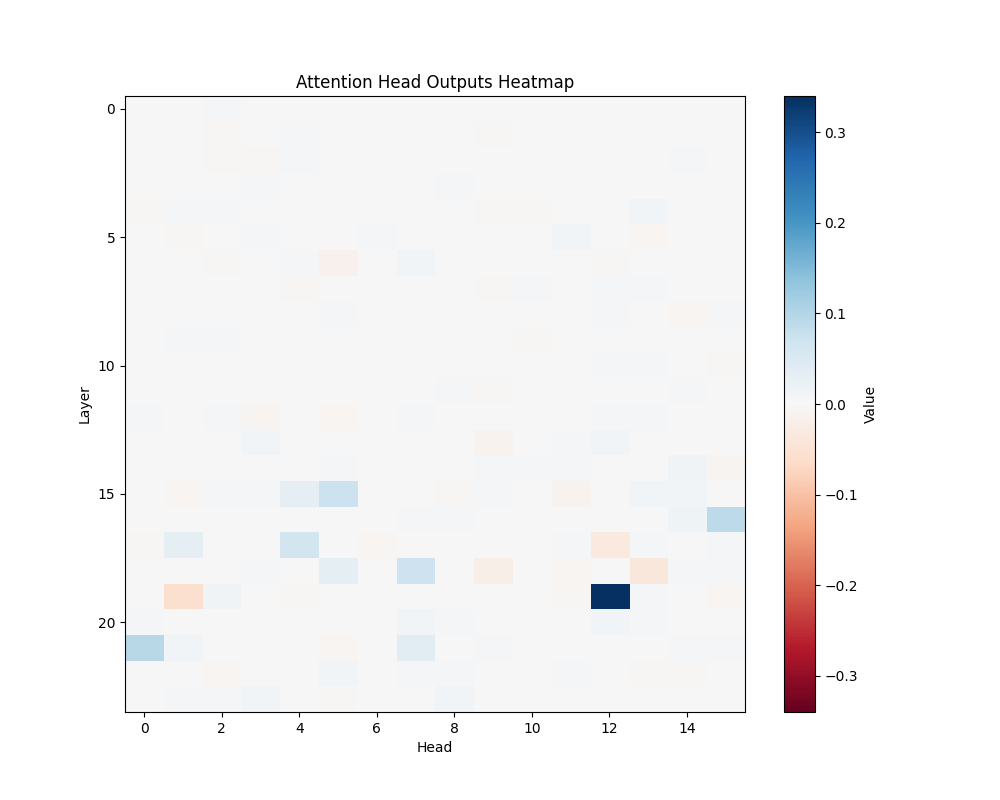

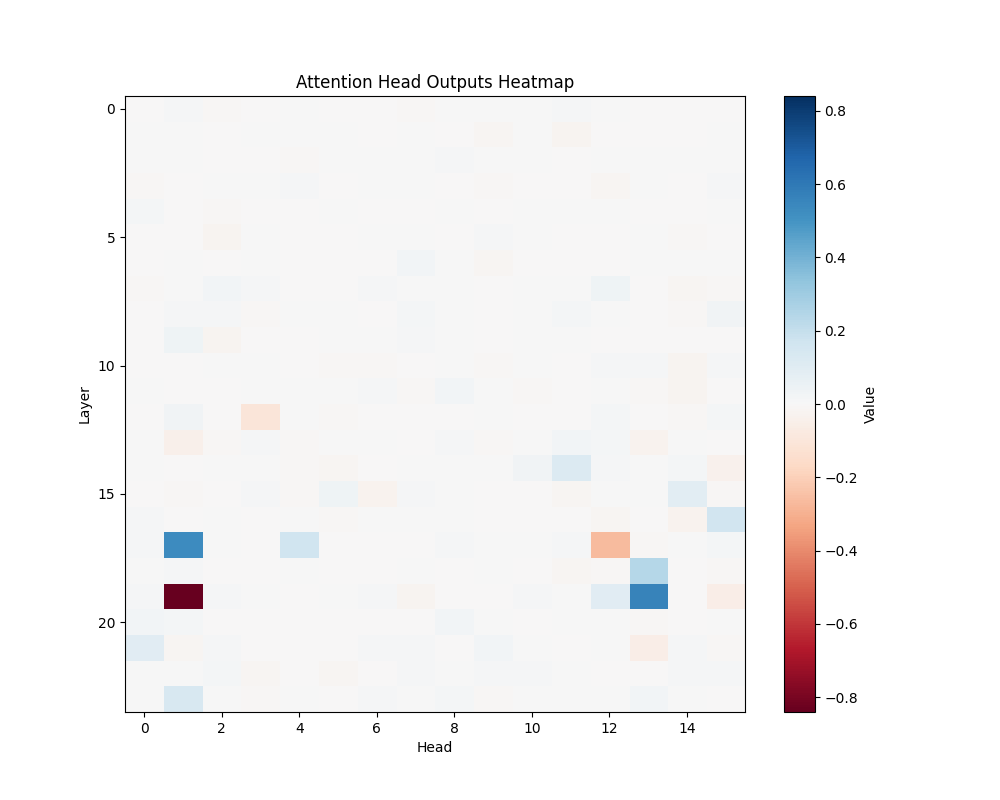

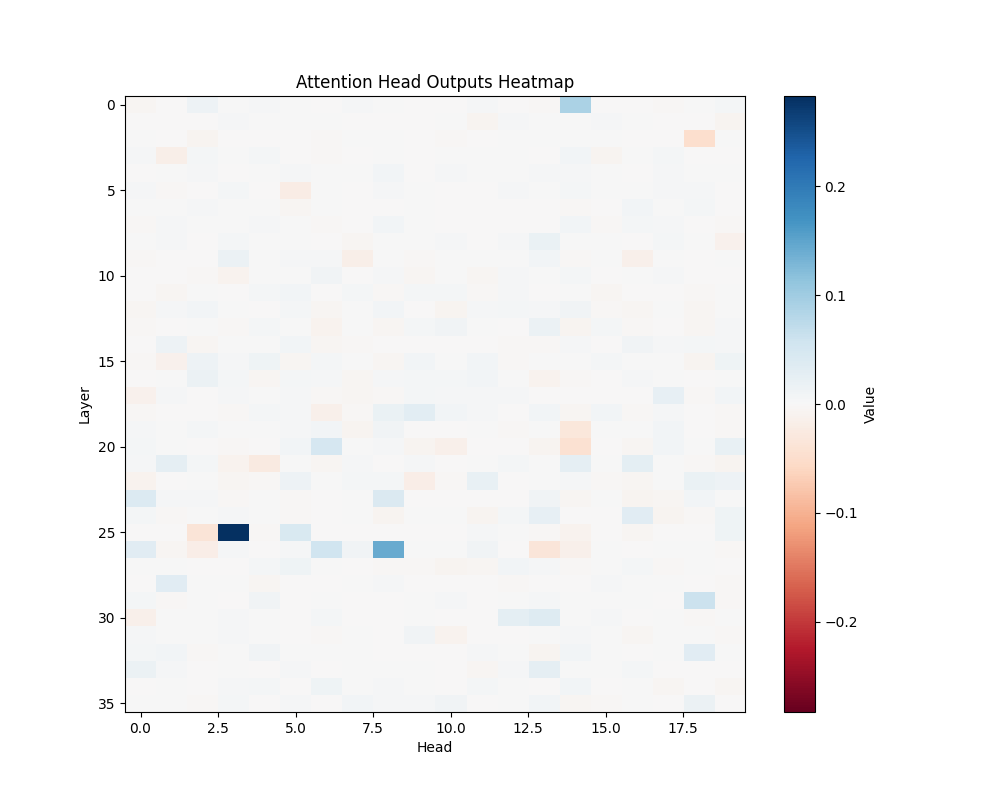

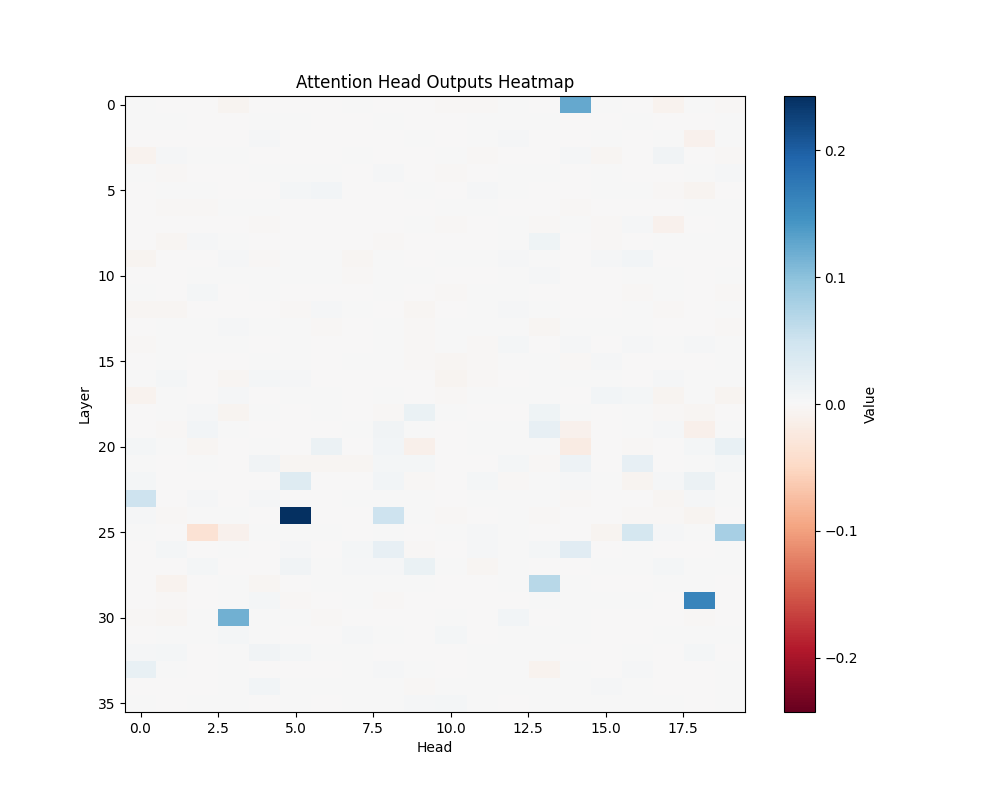

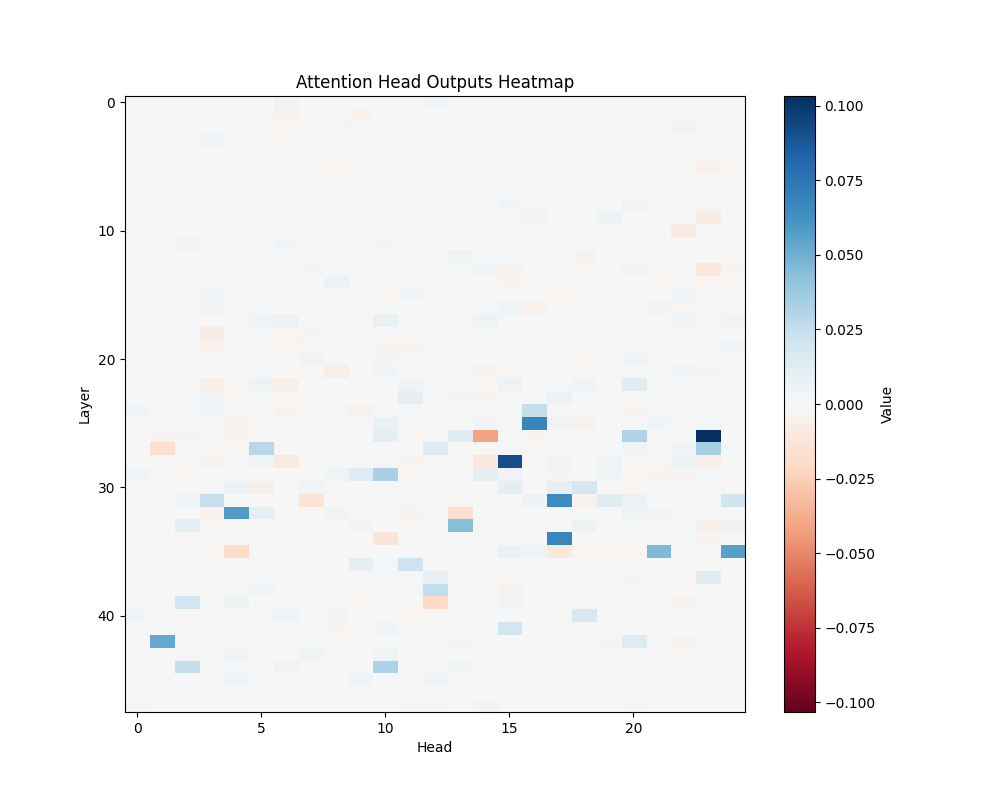

Figure 3: Average Semantic Attention Patterns Across Model Scales

GPT-2 Small | GPT-2 Medium |

GPT-2 Large | GPT-2 XL |

Key Circuits

GPT-2 Small (12 layers):

- Layer 8, Head 8

- Layer 10, Head 0

- Layer 10, Head 10

GPT-2 Medium (24 layers):

- Layer 19, Head 0

- Layer 13, Head 3

- Layers 20-22, Heads 14-15

GPT-2 Large (36 layers):

- Layer 30, Head 5

- Layer 25, Head 2

- Layer 35, Head 15

GPT-2 XL (48 layers):

- Layer 30, Head 5

- Layer 40, Head 20

- Layers 25-35, Heads 15-18

Discussion

The activation patching analysis reveals that semantic processing relies on specific attention heads that maintain consistent roles across different contexts. While smaller models concentrate semantic processing in a few powerful heads, larger models distribute this functionality across interconnected circuits. This architectural difference suggests a transition from single-point processing to more robust, distributed semantic analysis as models scale.

The presence of consistent activation patterns across different semantic contexts indicates these circuits are fundamental to the models’ semantic processing capabilities rather than artifacts of specific inputs.

Locating Mathematical Reasoning

Methods

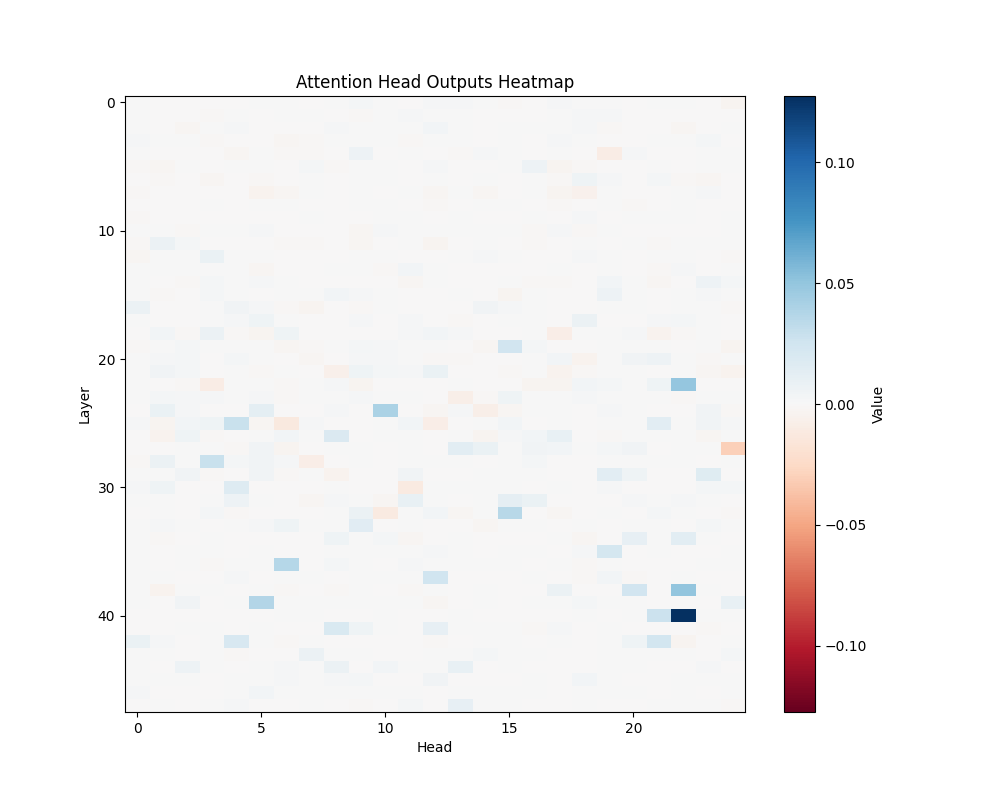

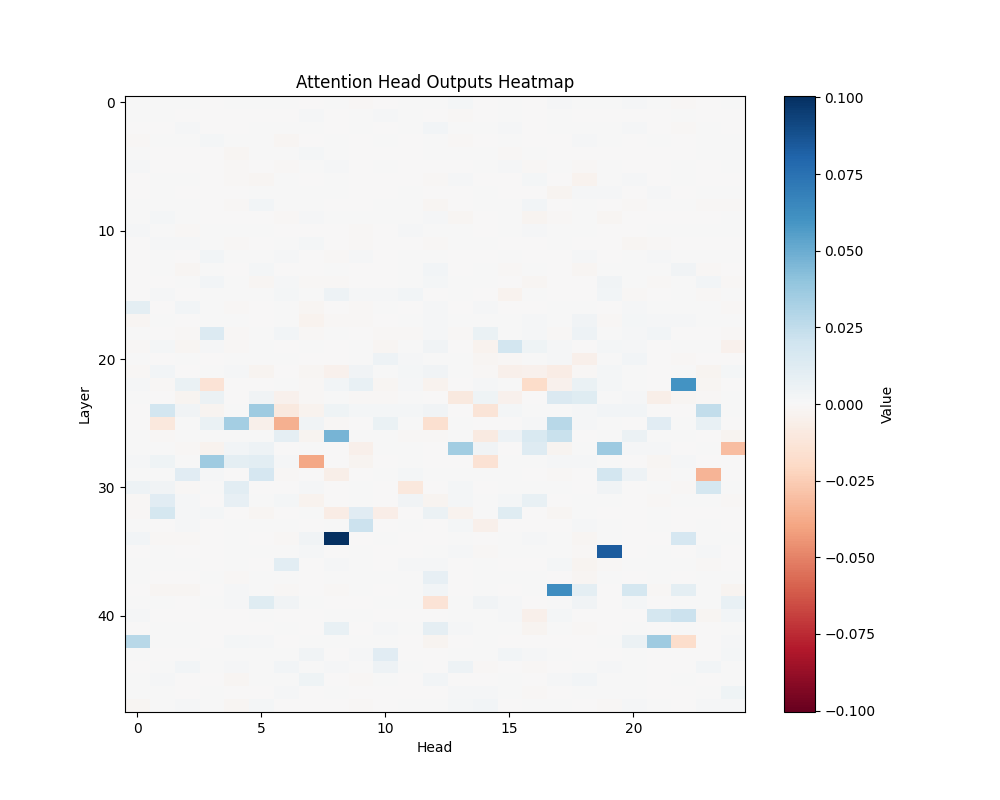

We performed activation patching analysis across GPT-2 variants to identify specific attention heads responsible for mathematical processing. Our analysis examined attention patterns when processing mathematical relationships, focusing on head-specific activations and their consistency across different mathematical contexts. The results shown here represent averages across all templates; individual template results can be found in Appendix C.

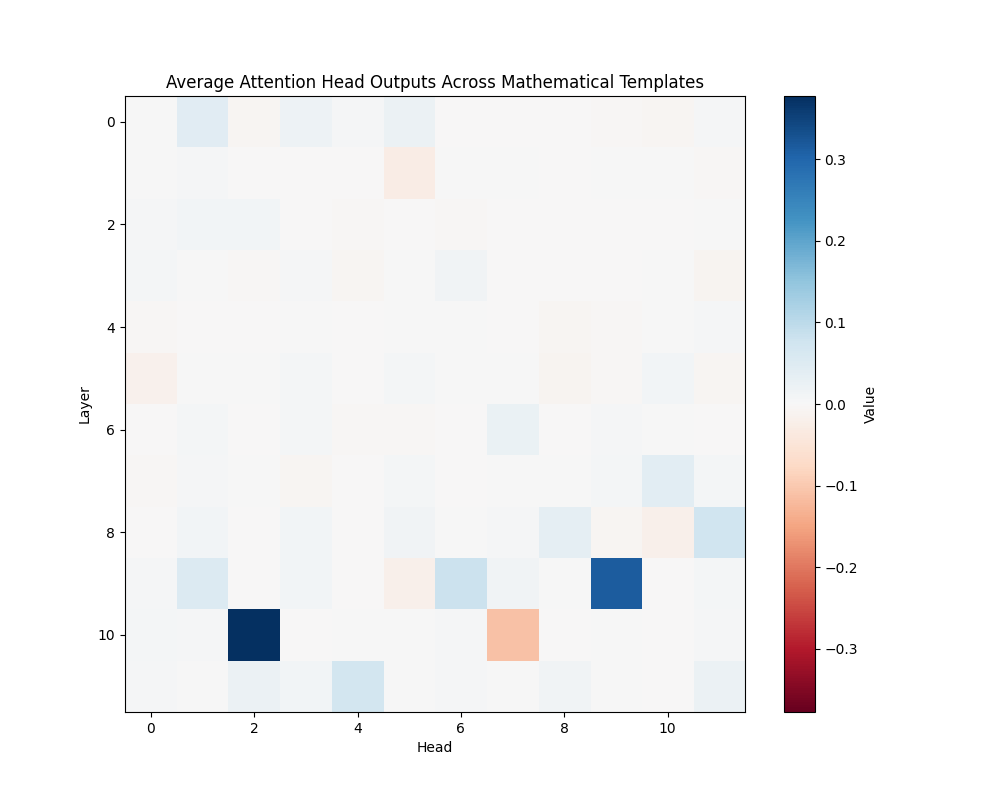

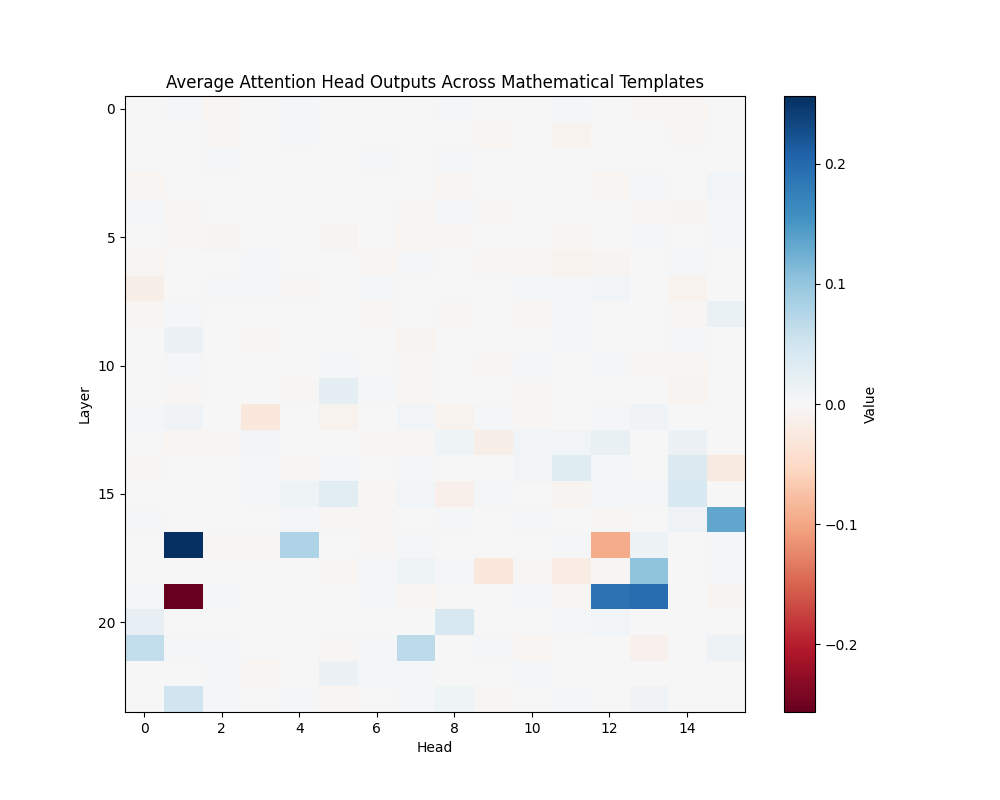

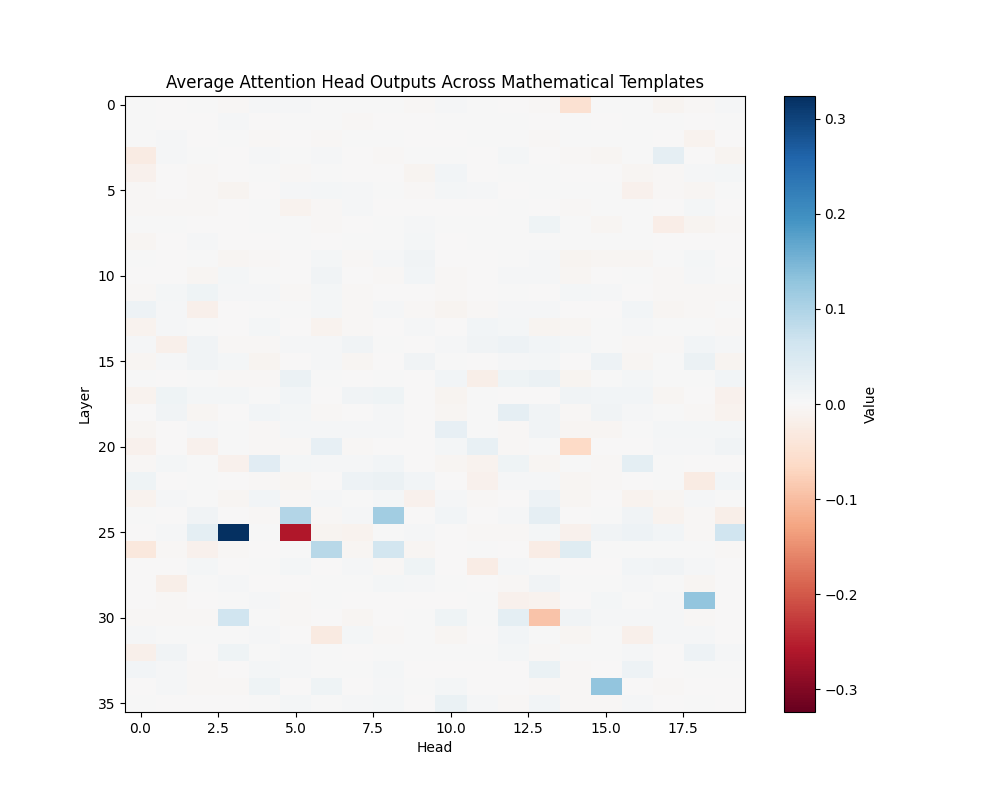

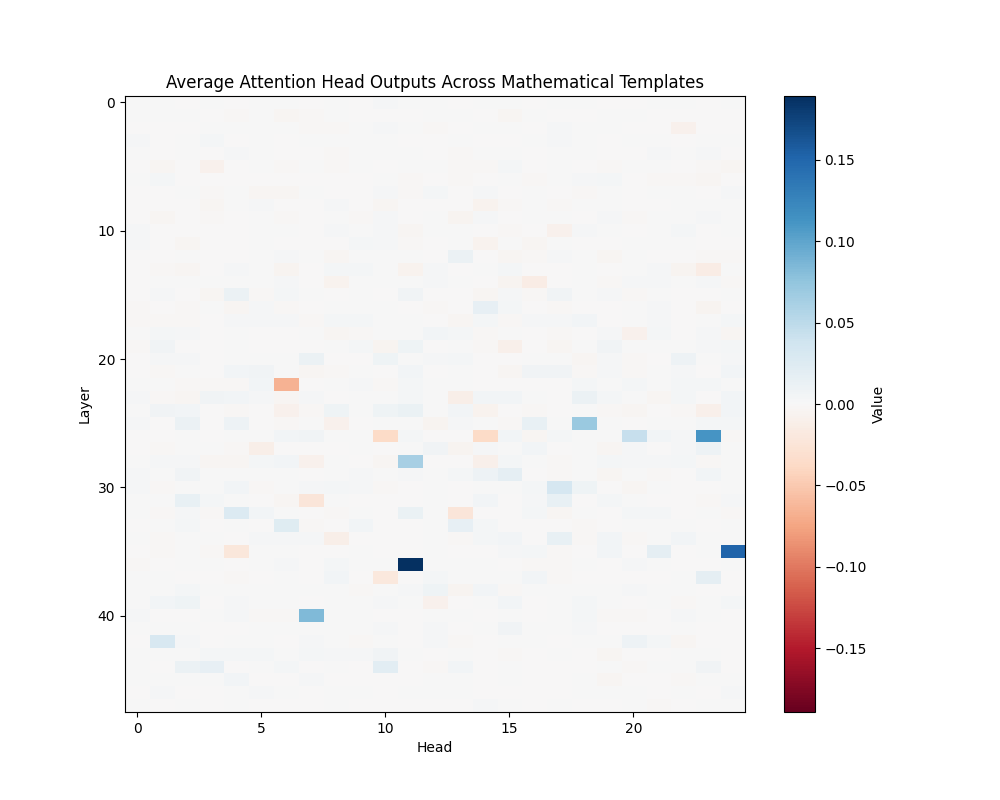

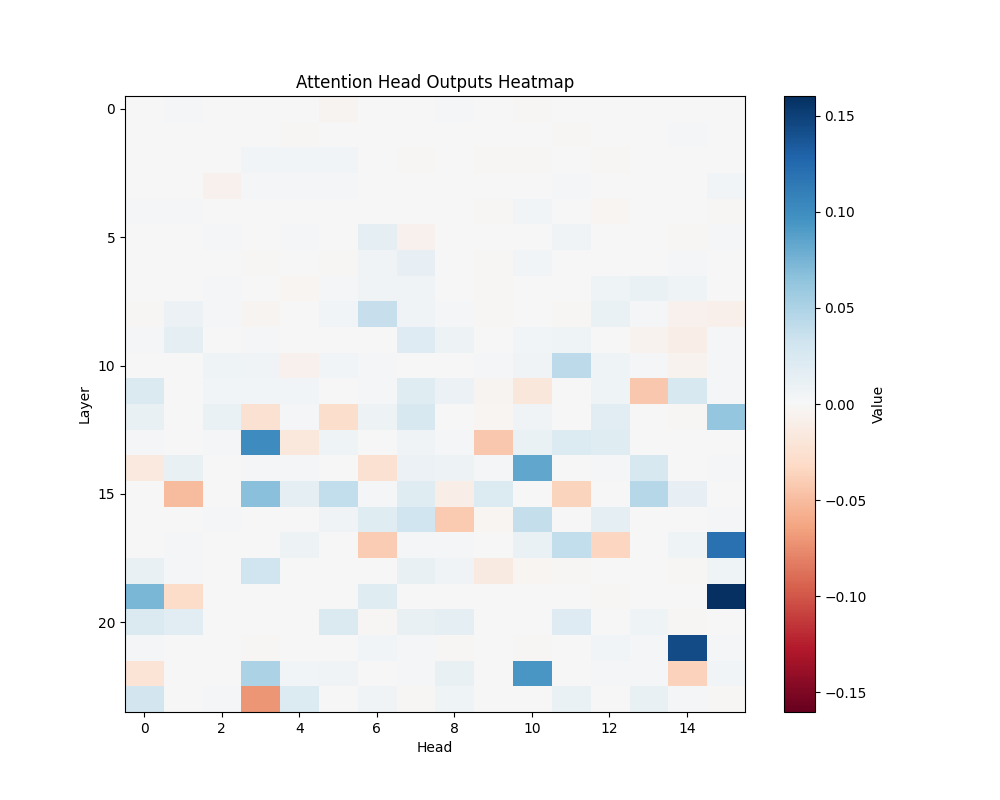

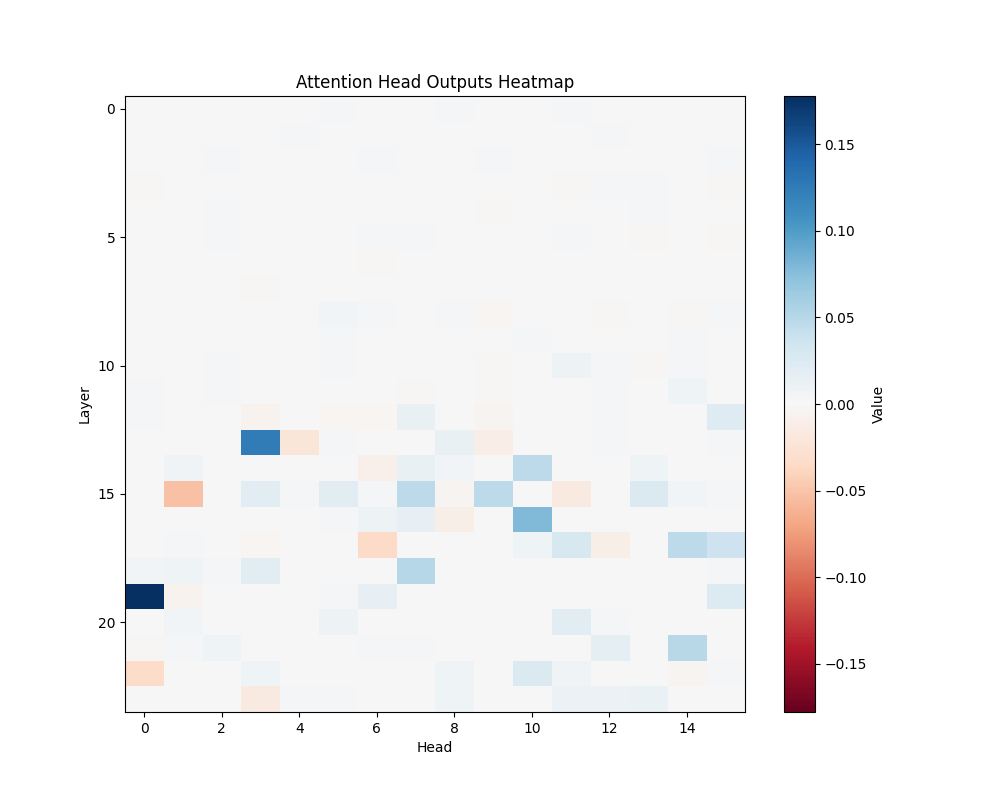

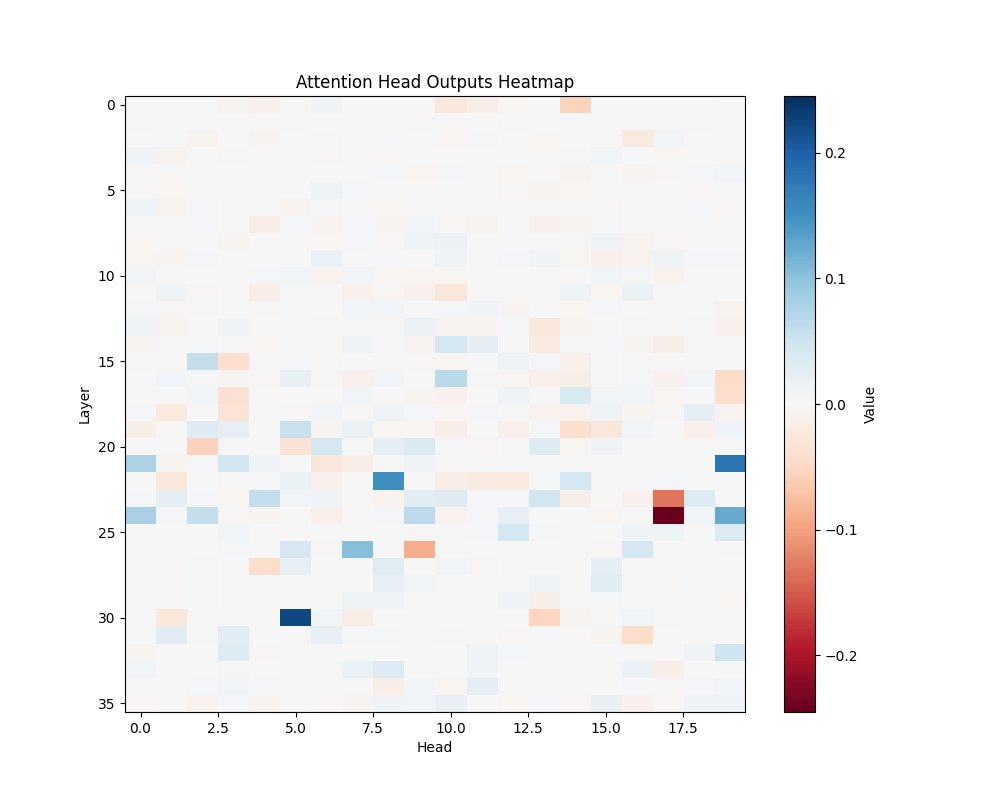

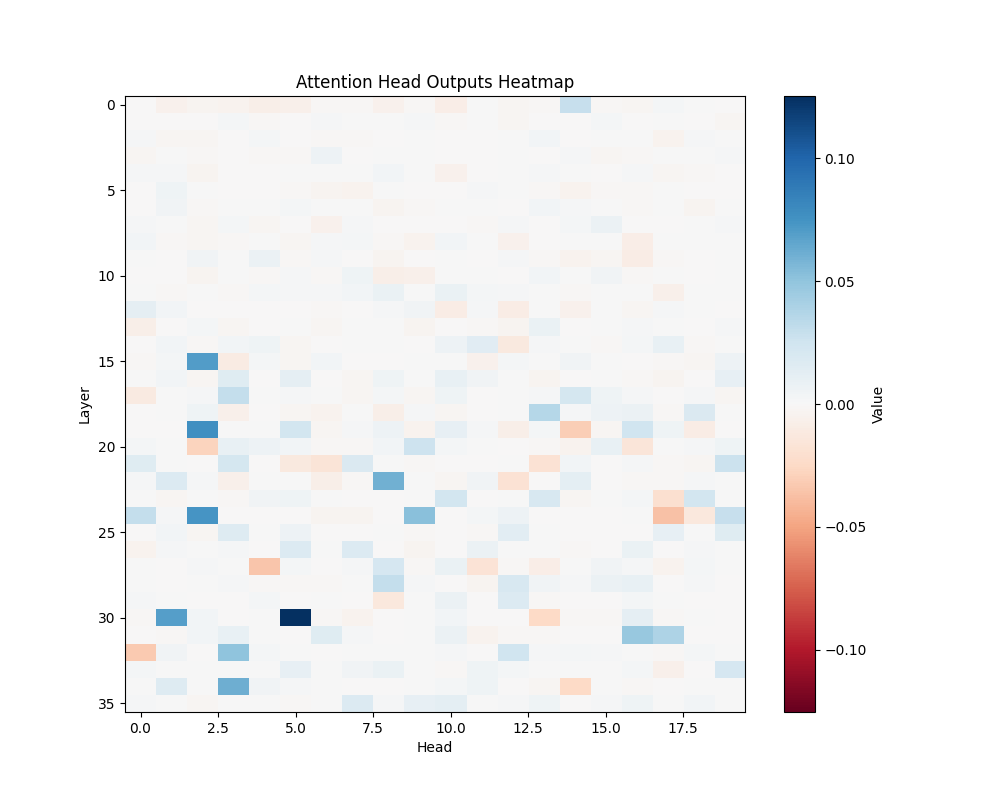

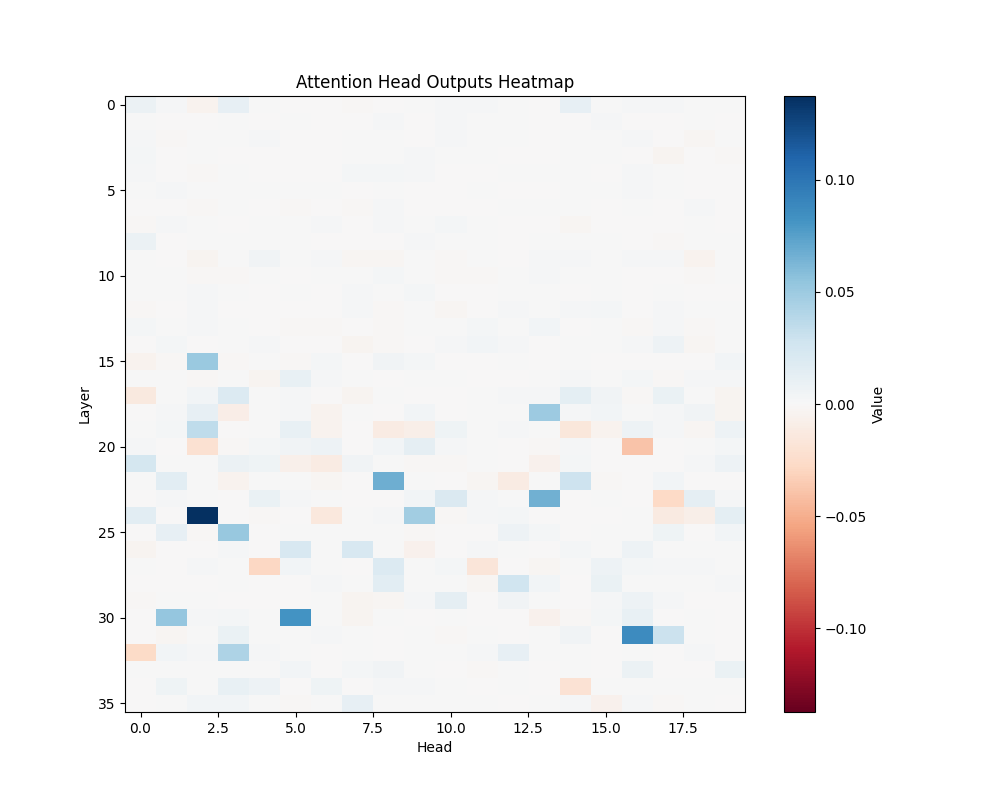

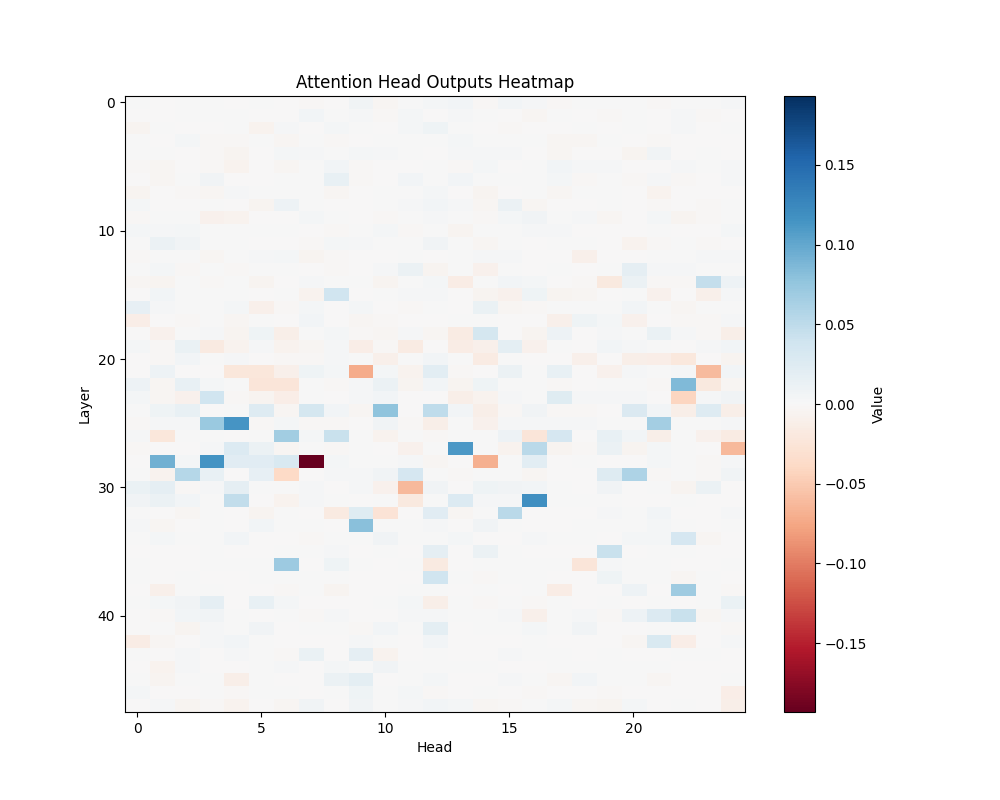

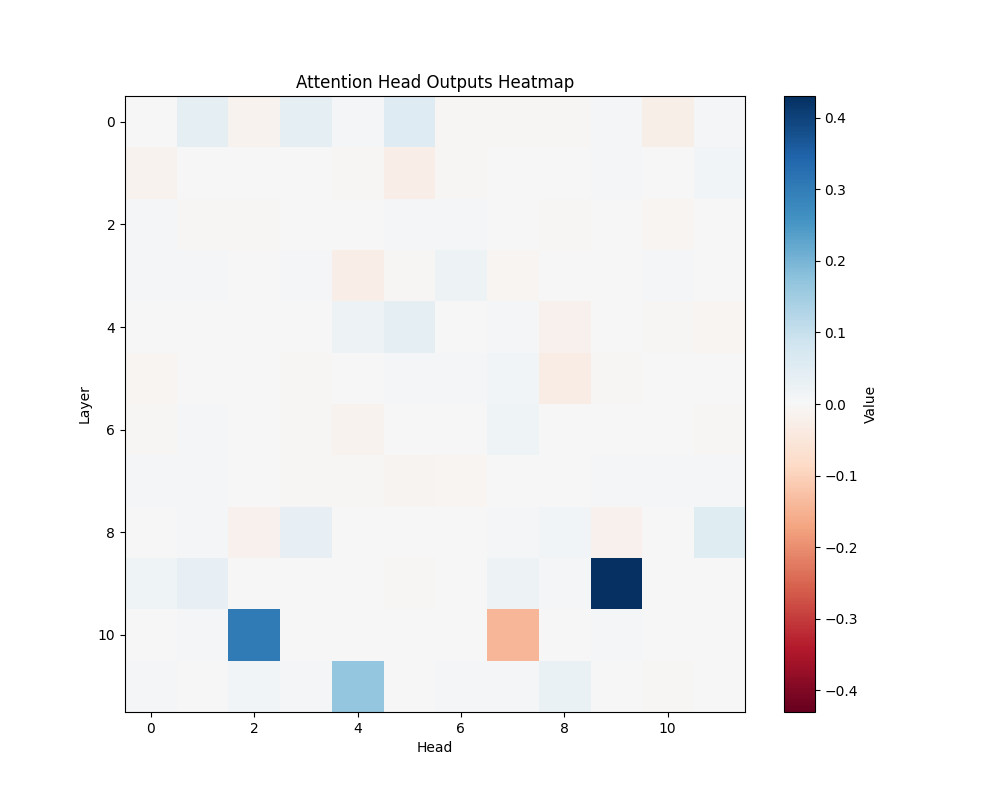

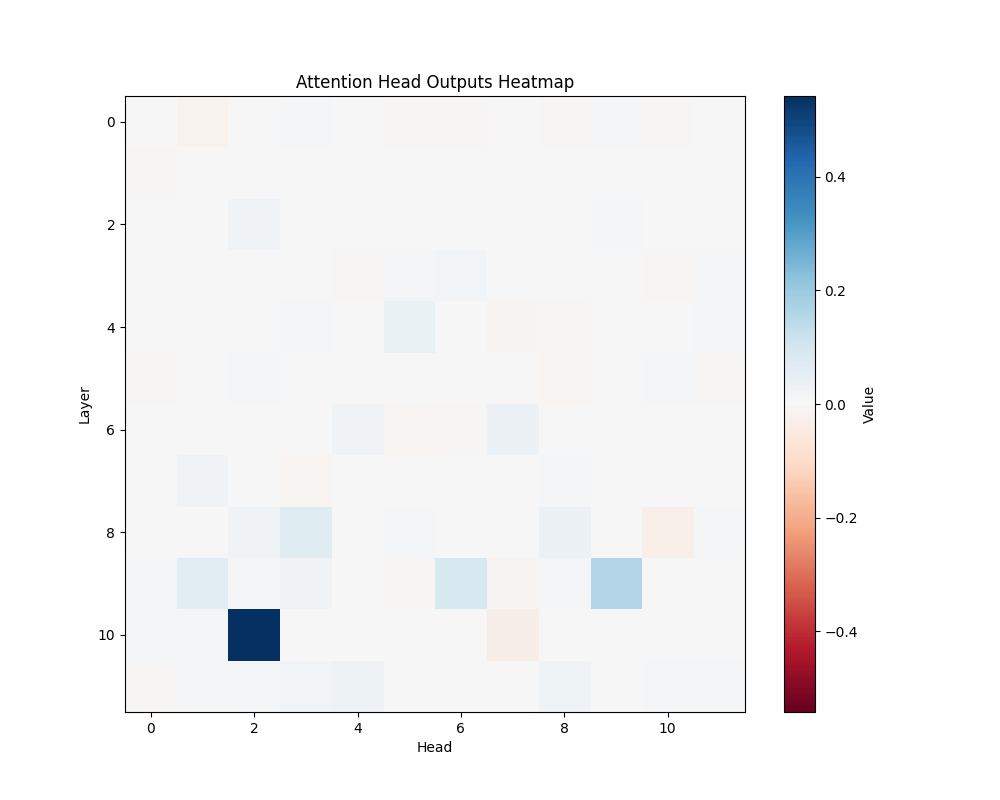

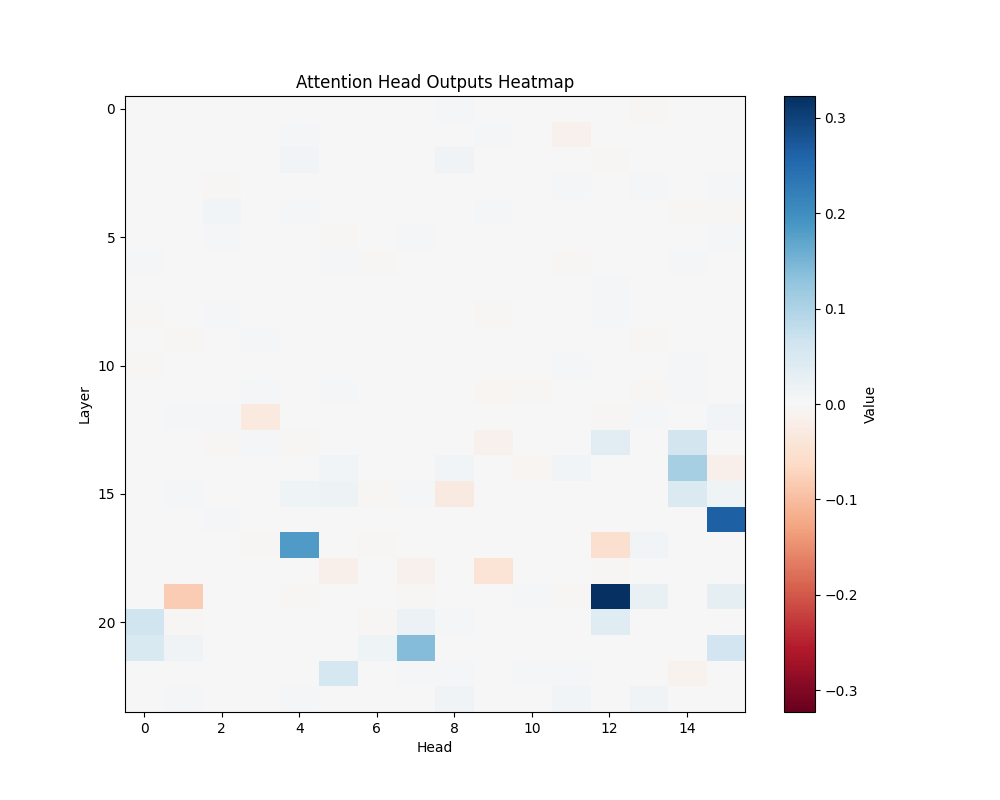

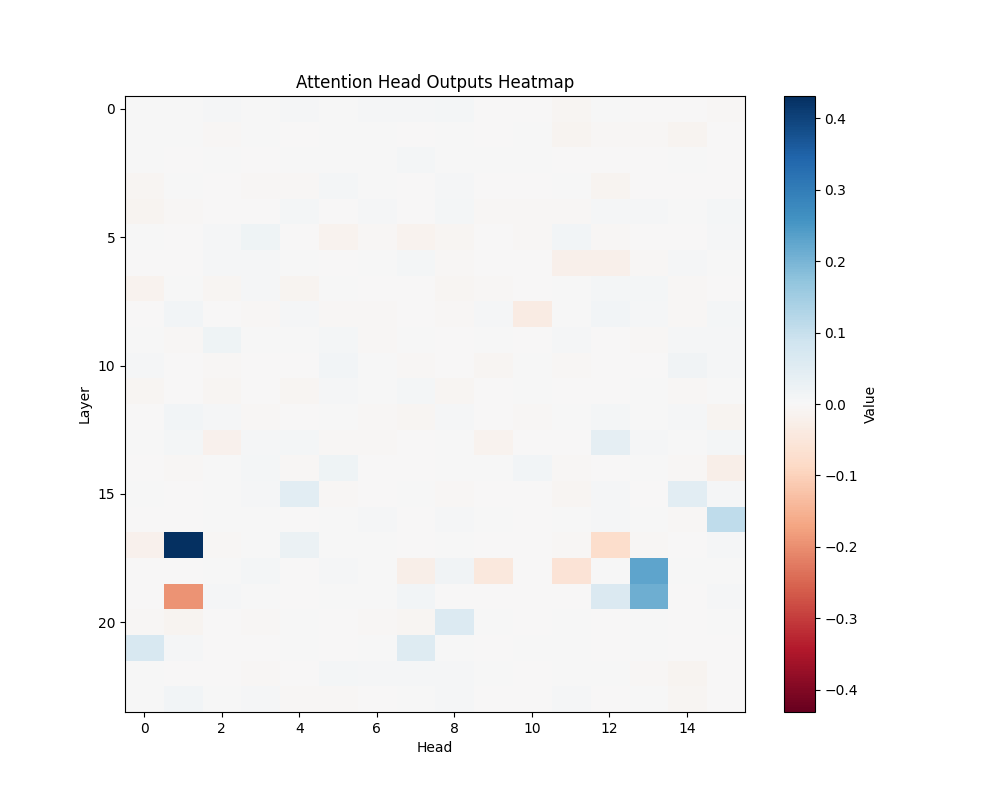

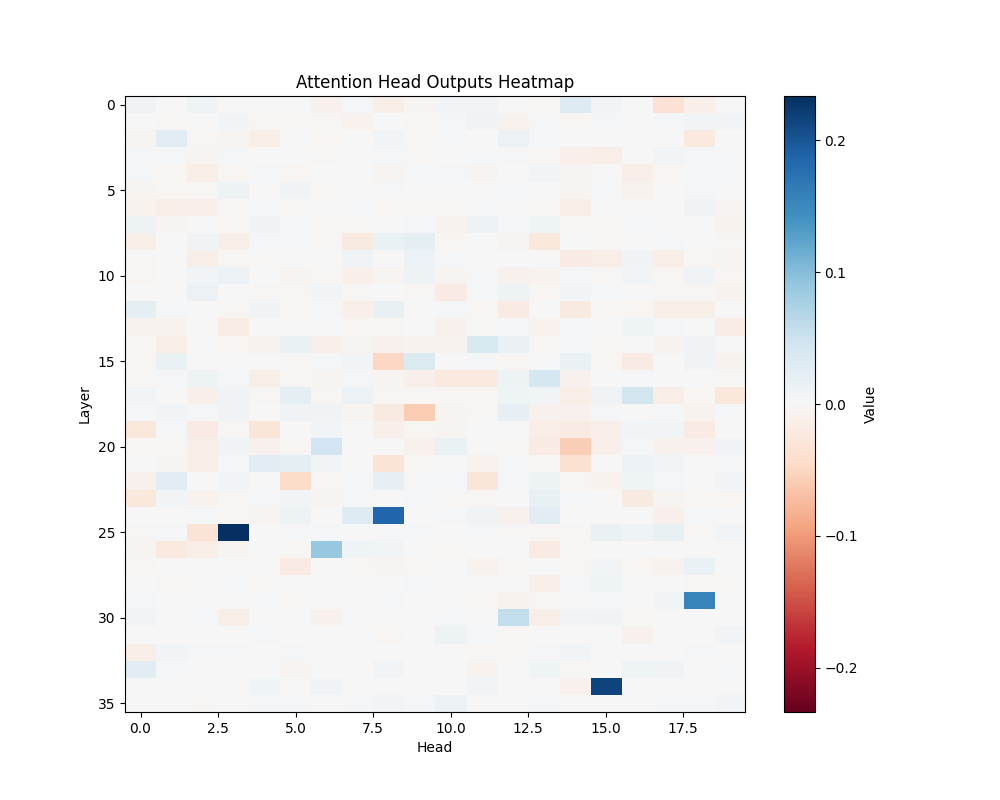

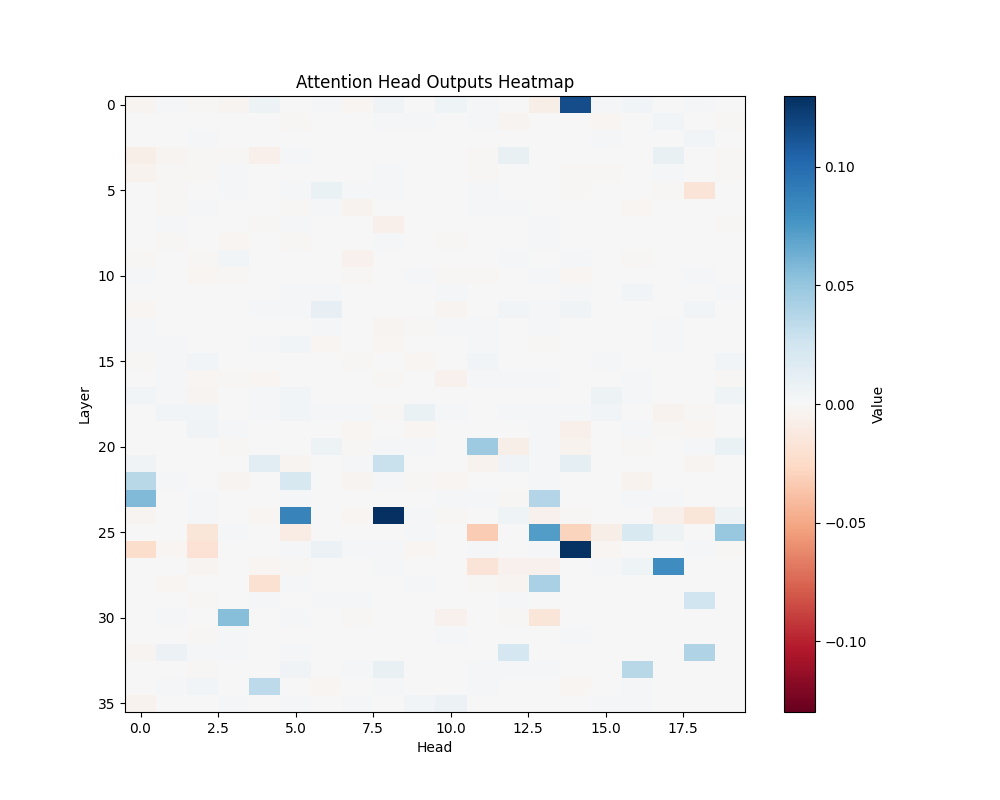

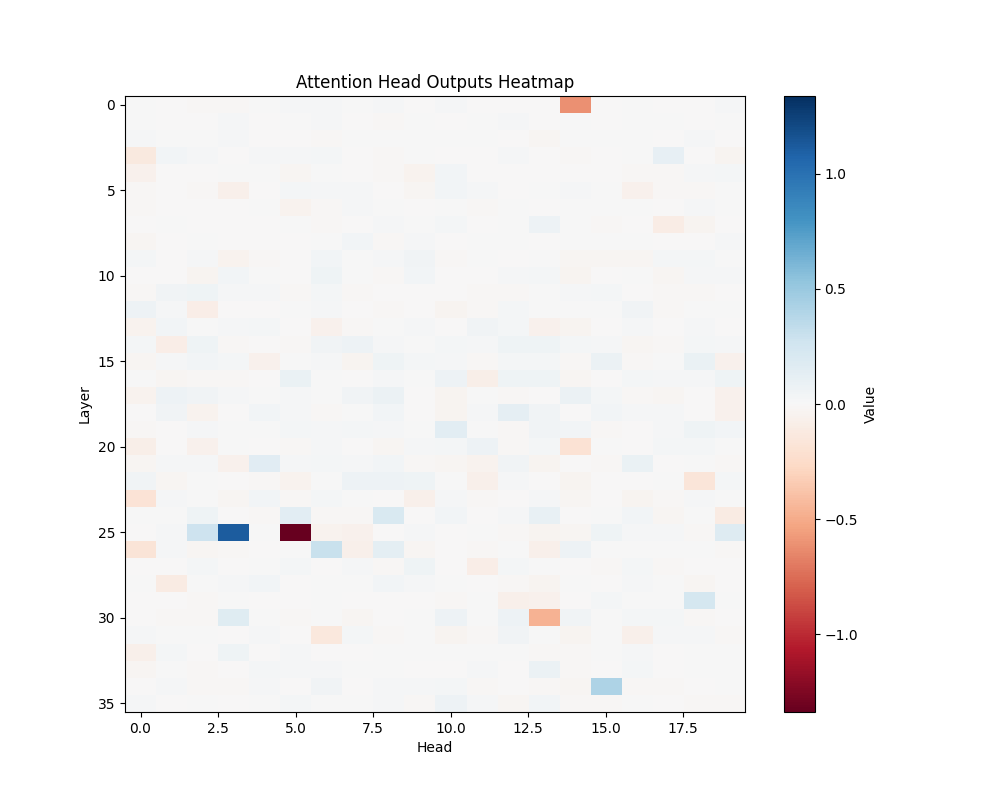

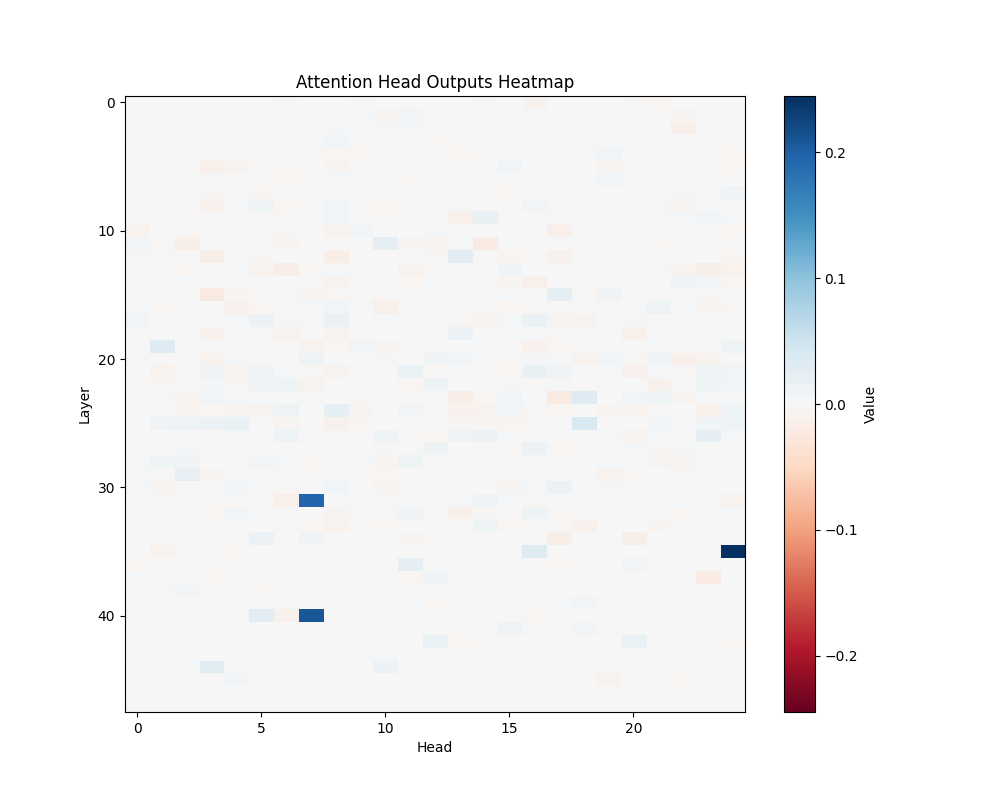

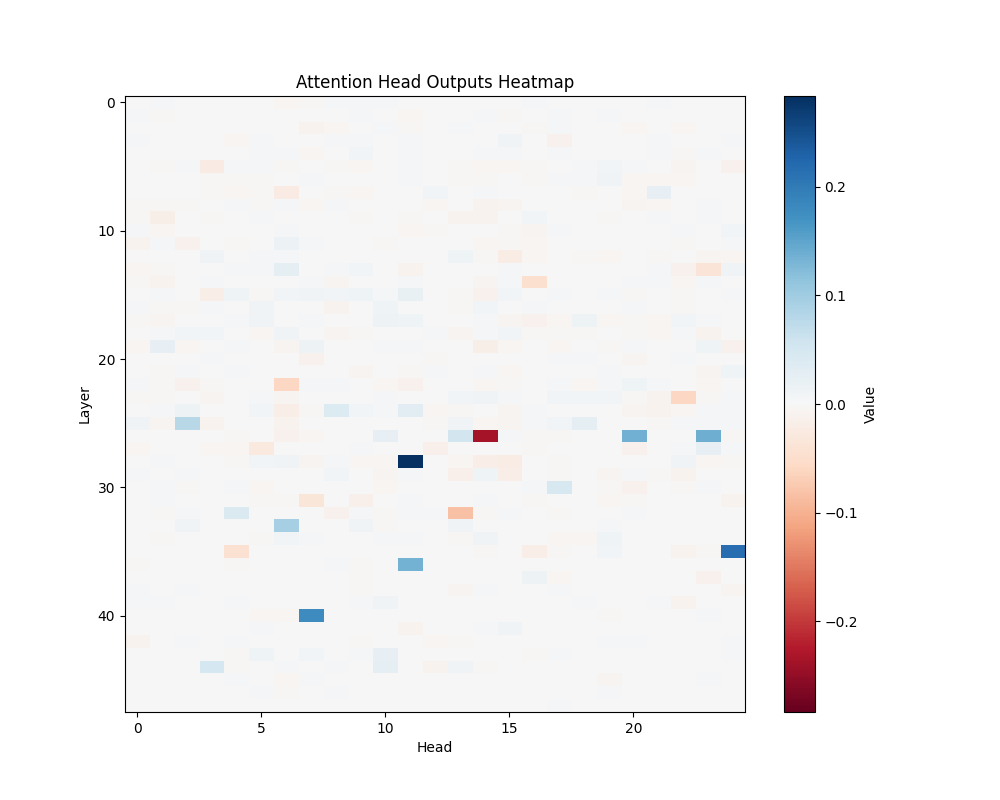

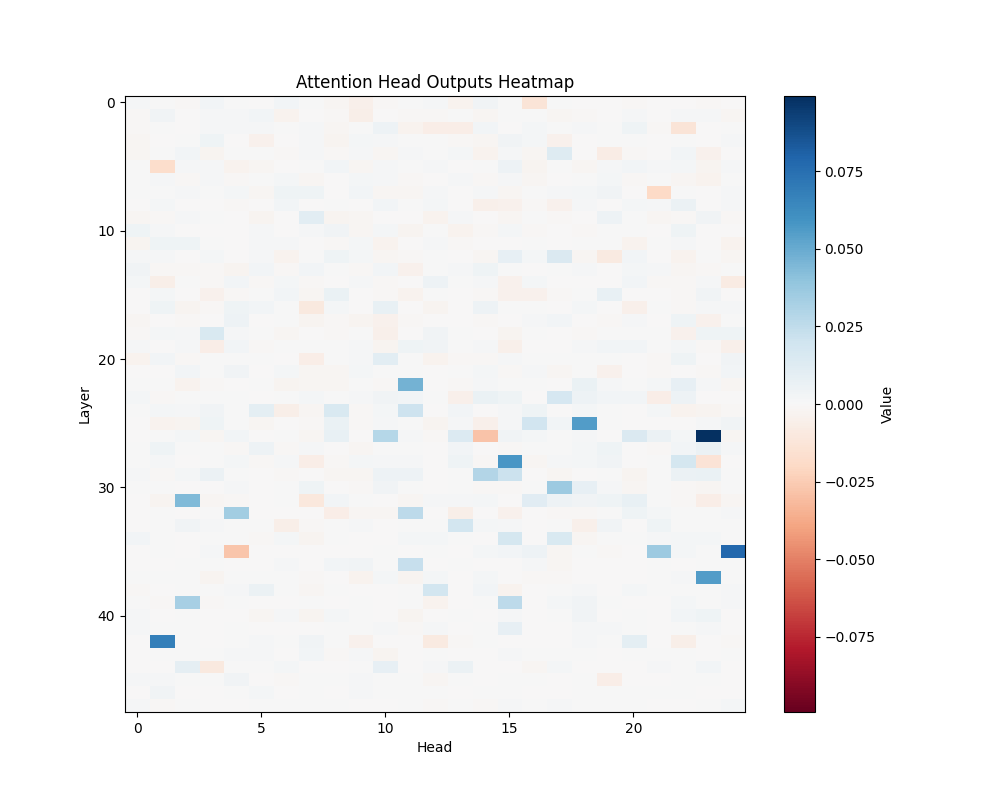

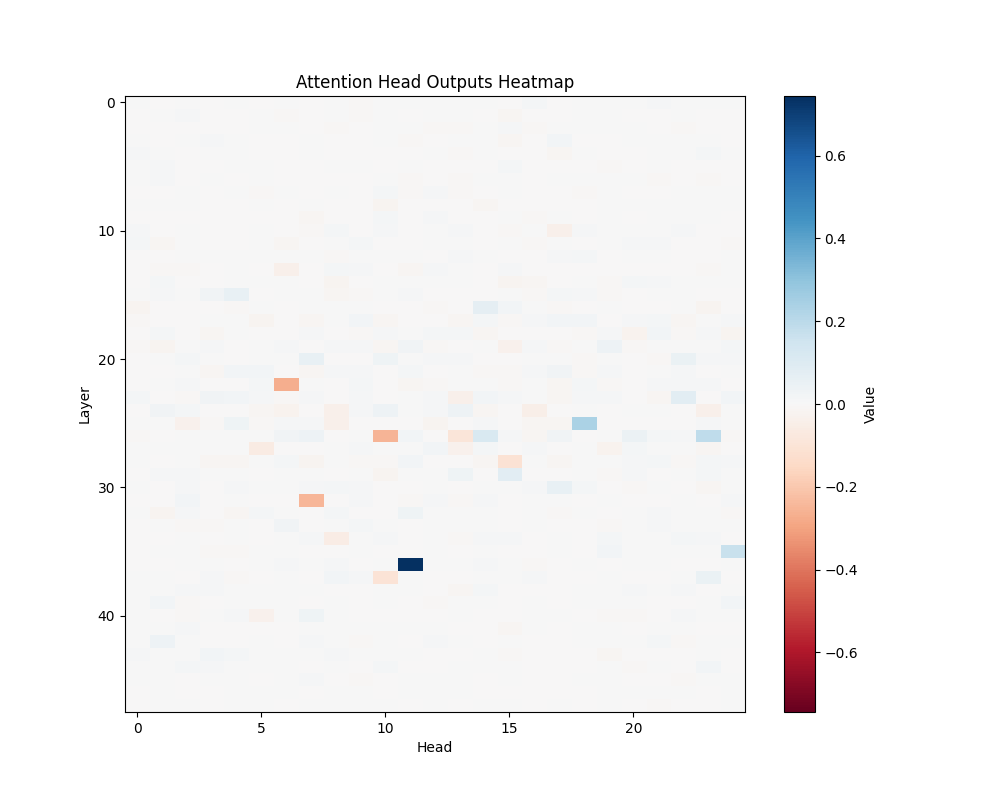

Figure 4: Average Mathematical Attention Patterns Across Model Scales

GPT-2 Small | GPT-2 Medium |

GPT-2 Large | GPT-2 XL |

Key Circuits

GPT-2 Small (12 layers):

- Layer 10, Head 2

- Layer 9, Head 8

- Layer 10, Head 6

GPT-2 Medium (24 layers):

- Layer 17, Head 0

- Layer 19, Head 12

- Layer 18, Head 13

GPT-2 Large (36 layers):

- Layer 25, Head 3

- Layer 25, Head 5

- Layer 24, Head 15

GPT-2 XL (48 layers):

- Layer 36, Head 11

- Layer 35, Head 20

- Layer 40, Heads 15-17

Discussion

The activation patching analysis reveals that mathematical processing relies on deeper layers compared to semantic and causal reasoning. While smaller models concentrate mathematical processing in a few powerful heads, larger models distribute this functionality across interconnected circuits. This architectural difference suggests a transition from single-point processing to more robust, distributed mathematical analysis as models scale.

The presence of consistent activation patterns across different mathematical contexts indicates these circuits are fundamental to the models’ mathematical processing capabilities rather than artifacts of specific inputs. The evolution from concentrated to distributed processing may explain larger models’ improved robustness in mathematical tasks.

Conclusion

Our comprehensive analysis of causal, semantic, and mathematical reasoning across different scales of GPT-2 models reveals several key insights about how these capabilities are implemented in transformer architectures:

- Hierarchical Processing Structure: Across all model scales, we observe a consistent hierarchical organization where:

- Early layers specialize in processing causal syntax (“because”, “so”)

- Deeper layers are recruited for semantic andmathematical reasoning

- Scale-Dependent Circuit Organization: As models increase in size, we observe a transition from concentrated to distributed processing:

- Smaller models (GPT-2 Small/Medium) rely on a few highly specialized attention heads

- Larger models (GPT-2 Large/XL) distribute computation across interconnected circuits

- This architectural shift may explain larger models’ improved robustness and performance

- Circuit Specialization: While some attention heads show task-specific specialization, we found minimal overlap between semantic and mathematical reasoning circuits, indicating that these capabilities rely on distinct mechanisms.

These findings advance our understanding of how transformer-based models implement different forms of reasoning and suggest that certain architectural principles, such as the early processing of syntax, may be fundamental to their operation. This work provides a foundation for future investigations into more complex reasoning capabilities and may inform the development of more interpretable and capable language models.

Future Work

- Investigate multi-step reasoning tasks.

- Investigate reasoning tasks with more complex causal relationships

- Extend analysis to larger LLMs.

- Investigate causal reasoning on reasoning focused LLMs.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted as part of the AI Safety Fundamentals: AI Alignment Course by BlueDot Impact. Special thanks to my facilitator and peers for their valuable feedback and discussions.

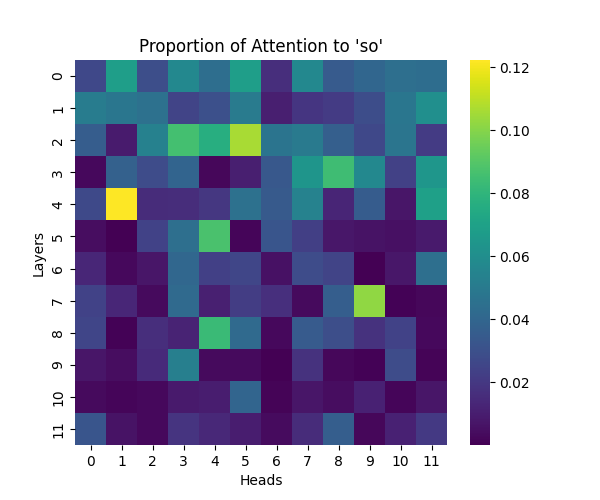

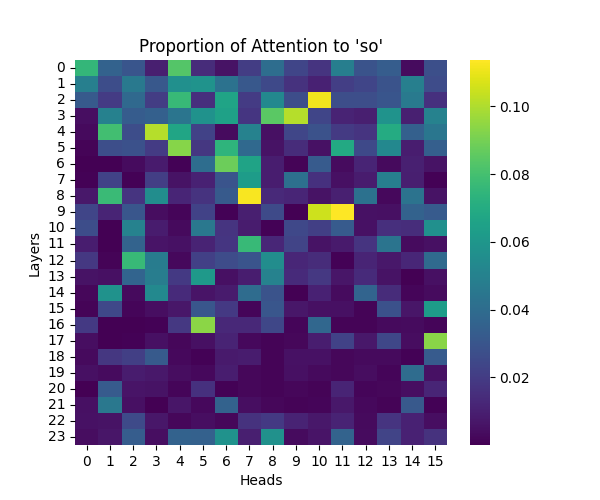

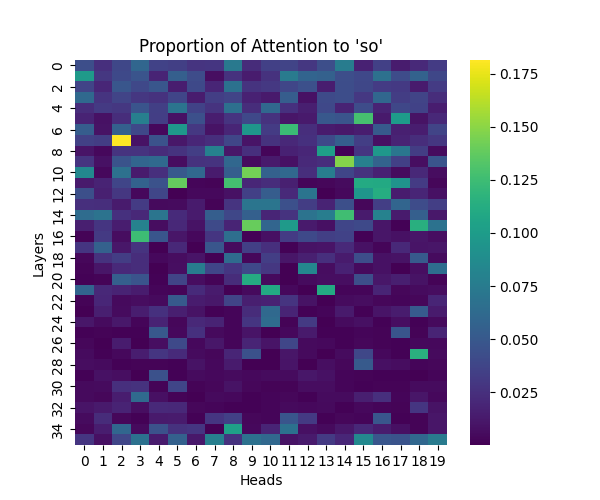

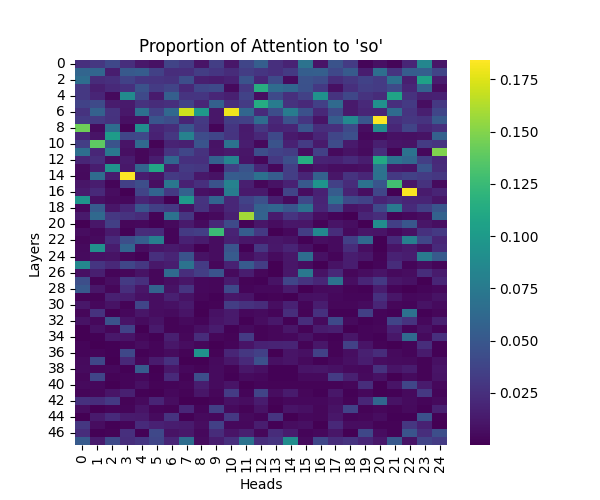

Appendix A: Analysis of “So” Causal Marker

Our analysis of the “so” causal marker revealed similar processing patterns to “because”, while maintaining similar scaling trends across model sizes.

Figure A1: Attention to “So” Token Across Model Scales

GPT-2 Small | GPT-2 Medium |

GPT-2 Large | GPT-2 XL |

Figure A2: Cause-to-Effect Attention Patterns Across Model Scales

GPT-2 Small | GPT-2 Medium |

GPT-2 Large | GPT-2 XL |

Appendix B: Per-Template Semantic Processing Results

Our main analysis presents averaged results across all semantic templates. Here, we break down the activation patterns for each template type to demonstrate the consistency of our findings.

Template Types

- Action-Location-Because (ALB): “John had to [action] because he is going to the [location]”

- Examples: “dress/show”, “shave/meeting”, “study/exam”

- Tests causal relationships between actions and destinations

- Action-Object-Because (AOB): “Jane will [action] it because John is getting the [object]”

- Examples: “read/book”, “eat/food”, “slice/bread”

- Tests causal relationships between actions and objects

- Action-Location-So (ALS & ALS-2):

- ALS: “Mary went to the [location] so she wants to [action]”

- ALS-2: “Nadia will be at the [location] so she will [action]”

- Examples: “store/shop”, “church/pray”, “airport/fly”

- Tests location-driven behavioral intentions

- Action-Object-So (AOS): “Sara wanted to [action] so Mark decided to get the [object]”

- Examples: “study/book”, “paint/canvas”, “write/pen”

- Tests object requirements for intended actions

Individual Template Results

GPT-2 Small Activation Patterns

ALB | AOB |

ALS | ALS-2 |

AOS |

GPT-2 Medium Activation Patterns

ALB | AOB |

ALS | ALS-2 |

AOS |

GPT-2 Large Activation Patterns

ALB | AOB |

ALS | ALS-2 |

AOS |

GPT-2 XL Activation Patterns

ALB | AOB |

ALS | ALS-2 |

AOS |

Appendix C: Per-Template Mathematical Processing Results

Our main analysis presents averaged results across all mathematical templates. Here, we break down the activation patterns for each template type to demonstrate the consistency of our findings.

Template Types

- Basic Addition Templates

- MATH-B-1: “John had {X} apples but now has 10 because Mary gave him {Y}”

- MATH-B-2: “Tom started with {X} marbles but now has 8 because his friend gave him {Y}”

- Tests understanding of addition through story problems

- Example pairs: [1,9], [8,2], [6,4], etc.

- Subtraction Templates

- MATH-S-1: “Alice had {X} cookies so after eating 2 she now has {Y}”

- MATH-S-2: “Bob had {X} dollars so after buying a toy for 3 dollars he has {Y}”

- MATH-S-3: “Sarah has {X} candies so after giving 4 to her friend she has {Y}”

- Tests understanding of subtraction through story problems

- Example pairs: [5,3], [7,5], [4,2], etc.

Individual Template Results

GPT-2 Small Activation Patterns

MATH-B-1 | MATH-B-2 |

MATH-S-1 | MATH-S-2 |

MATH-S-3 |

GPT-2 Medium Activation Patterns

MATH-B-1 | MATH-B-2 |

MATH-S-1 | MATH-S-2 |

MATH-S-3 |

GPT-2 Large Activation Patterns

MATH-B-1 | MATH-B-2 |

MATH-S-1 | MATH-S-2 |

MATH-S-3 |

GPT-2 XL Activation Patterns

MATH-B-1 | MATH-B-2 |

MATH-S-1 | MATH-S-2 |

MATH-S-3 |